Silver Fox Behaviour

As foxes are solitary predators, they do not live and hunt in socially structured groups or ‘packs’ the same way other canines do. Instead, they are socially select, forming individual territories and strong social relationships with family members and familiar individuals from neighbouring territories. Their social behaviour varies between individuals and can depend on the density of animals, availability of food sources and just plain personal preference.

Foxes adapt to group living through the development of social structures, using agonistic behaviours to establish and maintain simple dominance hierarchy's, which can change and alter over time. Foxes have their own social guidelines, attitudes, rituals and friendship criteria - which, for the most part seems to boil down to; 'what mum says goes', 'mine' and 'live and let live'.

All foxes have unique personalities. Some foxes enjoy the company of others and will form stable social bonds, some do not. Some foxes are bold, while others are much more timid. While silver foxes are social creatures, in free-living environments (such as those at sanctuaries, breeders, educational zoo's and attractions, they retain their solitary predatory instincts and can be divided into those who prefer to form social bonds and those that prefer to remain solitary, with their own individual territory.

Unlike dogs, foxes are much less inclined to follow the commands of a leader and are much more like cats, with respects to their behaviour towards territorial needs and their conspecifics. Training and behavioural modification must take into respect the differences between the behaviour foxes and other canines.

It is also important to note that ‘pack mentality’ does not exist in foxes, so it cannot be used as a management tool. Foxes live by the philosophy 'every man for himself' and will take every advantage presented to them that takes their fancy. If you try to dominate and control a fox against its will, it will flee or fight back.

Silver foxes that were experimentally domesticated for tameness show much more social behaviour towards humans, similar to that of dogs, but these foxes also retain their natural solitary hunting lifestyle.

"We show here that fox kits from an experimental population selectively bred over 45 years to approach humans fearlessly and non-aggressively... are not only as skilful as dog puppies in using human gestures but are also more skilled than fox kits from a second, control population not bred for tame behaviour...

These results suggest that socio-cognitive evolution has occurred in the experimental foxes, and possibly domestic dogs, as a correlated by-product of selection on systems mediating fear and aggression, and it is likely the observed social cognitive evolution did not require direct selection for improved social cognitive ability."

It has also been reported that;

"On average, the domestic foxes respond to sound two days earlier and open their eyes one day earlier than their non-domesticated cousins. More striking is that their socialisation period has greatly increased. Instead of developing fear responses at 6 weeks of age, domestic foxes didn't show it until 9 weeks of age or later, [fear responses develop at 3-5 weeks in wild foxes]. The whimpering and tail wagging is a holdover from puppyhood, as are the foreshortened face and muzzle. Even the new coat colours can be explained by the altered timing of development."

Free Ranging Dogs - Stray, Feral or Wild? Experimental Evidence - Guillaume de Lavigne

The Importance of Territory

Like cats, foxes are essentially solitary hunters and it is important for them to establish a territory that avoids conflict with other foxes. Foxes do this by using territorial marking at strategic points within their territory (depositing urine, faeces and scent from both facial and anal glands), as well as from chewing and digging due to the scent glands in their mouths and on on their paws. This allows them to communicate indirectly and minimizes direct conflict.

Foxes are primarily crepuscular, with a tendency towards more nocturnal behaviour, being more active from midnight to dawn. A wild fox will travel an average of 5-10 miles a night within their home range, revisiting some sites several times a night. Their territory focuses around a ‘den’ area or ‘earth’; which is a space secure enough to sleep, eat, play and potentially socialise. However, some foxes prefer to use sheltered sites such as stumps, hollow logs or dense vegetation and can use several resting sites within their home range, which means they will not necessarily return to the same site each day.

The territories of wild foxes can alter depending on the time of year and ‘neutral zones’ develop where territories overlap . If an unwanted fox encroaches into another’s territory it will provoke an aggressive interaction to defend resources and expel the intruder. Firstly through vocalisation and posturing, and if that is not effective, through a brief but noisy attack.

The ability to adapt and move around territories is an important survival tool for foxes, supporting "many ecological processes, including gene flow, population regulation, and disease epidemiology", yet full data on these behaviours is lacking.

We do know that wild foxes exhibit 2 periods of ‘extraterritorial movements’:

- When an individual leaves the maternal home territory.

- When males search for females during breeding season.

"Foxes making reproductive movements travelled farther than when undertaking other types of movement, and dispersal movements were straighter. Reproductive and dispersal movements were faster than territorial movements and also differed in intensity of search and thoroughness. Foxes making dispersal movements avoided direct contact with territorial adults and moved through peripheral areas of territories. The converse was true for reproductive movements. Although similar in some basic characteristics, dispersal and reproductive movements are fundamentally different both behaviourally and spatially"

In wild foxes, population density and territory size vary considerably. Such adaptable behaviour allows the fox to maintain a healthy, stable population. Hunting is used as a method to reduce the numbers of wild foxes where population densities are high, however, it is thought that hunting only aids to increase population figures, as once a fox is removed from it's territory, neighbouring foxes will move into the unclaimed territory, especially in high density areas.

"Red Fox density is highly variable. In the UK, density varies between one fox per 40 km²... but can be as high as 30 foxes per km² in some urban areas where food is superabundant... Social group density is one family per km² in farmland, but may vary between 0.2-5 families per km² in the suburbs and as few as a single family per 10 km² in barren uplands... The pre-breeding British fox population totals an estimated 240,000... Mean number of foxes killed per unit area by gamekeepers has increased steadily since the early 1960s in 10/10 regional subdivisions of Britain, but it is not clear to what extent this reflects an increase in fox abundance"

Vulpes Vulpes: Population - ICUN Red List of Threatened Species, 2015

It is advised that captive foxes are housed in a minimum of 150 square foot per fox and that they are housed individually or in pairs (individually housed captive-bred foxes will require lots of human contact).

"Creating enclosures in wildlife rehabilitation centres contributes to a large fraction of the success of a wildlife rehabilitator. The standards given by the National Wildlife Rehabilitation Association (NWRA) in enclosure design for red foxes (1.2m x 1.2m x 2.4m) are too small to truly benefit these animals once released.

In 2017, a 4.57m x 3.05m x 2.44m enclosure was designed and built to exceed the 2012 NWRA standards for housing of juvenile red foxes. Between 2017 and 2018, behaviour and welfare were tested through observational ethograms and compared amongst 2 separate groups of foxes. Frequency of behaviours were compared between both years and overall behavioural development differed. Even though as adults red foxes are quite solitary, results indicated as juveniles, living in a socialized group encouraged a more harmonized behavioural development.

The frequencies were consistent, with many passive behaviours occurring (lying down, hiding). Feeding time brought about a social hierarchy and competition, encouraging faster natural development. When living in a singular environment, all natural behaviours developed within the same timeframe as previous. However, fewer passive activities were observed and instead, behaviours were more active (running, walking, playing).

Feeding time exhibited less social competition and an even keel distribution of behaviour occurred. Enclosure design minimized stereotypical behaviours (pacing, panting) and encouraged natural development of behaviours overall prior to release. The analysis suggests that further extensive research should be conducted in relation to enclosure design and post-release tracking studies need to be performed to view the successfulness of these animals once released back into the wild."

Where temperaments and space allow, same-sex groups can be maintained with relative ease but it is important to note that foxes can suddenly 'fall out' and have a tendency to hold grudges, so if you group-house foxes, ensure you have emergency provisions available for such an event, should the animals ever need to be separated temporarily or even permanently.

Females dominate fox territories and often prefer to be housed alone or with few friends of their choosing, males tend to be more comfortable around others and are more suitable for group living in captivity. It is not advised to keep unneutered animals together and this is especially true for foxes as they can be very temperamental during dispersion and breeding season. Group-housed foxes will require adequate amounts of space, enrichment and access to resources in order to maintain peace. Neutering will reduce some of the seasonal hormonal surges that drive this behaviour but it will not eliminate it.

'October Crazies'

When raising cubs it is important to note that come dispersion season, captive-bred foxes may decide they no longer wish to live with their conspecifics any longer and fights may break out. Separate animals that are not getting along and ensure lots of enrichment and training is provided to ensure these highly active animals are stimulated throughout the day. Please see our enrichment page for more information.

"Relatedness between group members is central to understanding the causes of animal dispersal. In many group-living mammals this can be complicated as extra-pair copulations result in offspring having varying levels of relatedness to the dominant animals, leading to a potential conflict between male and female dominants over offspring dispersal strategies.

To avoid resource competition and inbreeding, dominant males might be expected to evict unrelated males and related females, whereas the reverse strategy would be expected for dominant females"

Mother Knows Best: Dominant Females Determine Offspring Dispersal in Red Foxes, 2011

This dispersion season is known as the 'October Crazies' to captive-bred fox keepers and is a period of gradually increasing social tension among fox families that begins in late summer and continues throughout autumn, just before the seasonal changes for breeding season occur over late winter.

The 'October Crazies' can be very prevalent in their first year and can occur each subsequent year. While foxes can be difficult to manage during these times, these seasonal dispersion and breeding changes tend to last only a few months per year and difficult behaviours tend to subside with age. It is important to maintain enrichment and training through these periods, just adjust any schedules to suit.

The dispersion period is characterised by aggressive and confrontational behaviour that is influenced by seasonally driven hormonal changes that ultimately ensures dispersal of family members and completion of the breeding cycle. It is this time of year (as well as during the breeding season), that captive-bred foxes are most prone to escape.

Naturally Social

It is not uncommon for foxes (particularly urban foxes), to share territory and form structured social groups of 3-8 foxes. This alliance is usually based around family connections and shared available resources. The collective term for a group of foxes is a ‘skulk’ or ‘leash’.

It is not guaranteed a fox will adopt such social living arrangements, some will continue to choose to live a more solitary life but small groups of co-operating family members may work together to raise cubs. In the wild it is subordinate females that will assist in raising cubs, forming strong social bonds and familiarity with individuals within the group at a young age, thus securing their place within the local territory.

Fox social structure is fluid and subject to change, so while there is a dominance hierarchy in such groups, the relationships are complex, with stronger affiliation between some foxes and less between others and relationships can be influenced by things such as; familiarity, relationship, age, health, season and resource availability.

Despite the ability to adapt well to group living, foxes do not develop social survival strategies nor do they posses or develop ‘pack mentality’. Even existing in such social groups, they remain solitary hunters and 'food aggression' may be prevalent. Where social groups of foxes do exist, they appear only to work well when the members of the group are familiar and when there is no competition over food or other resources.

"In urban fox families, mothers determine which cubs get to stay and which must leave, while fathers have little say in the matter"

In 2010, the social behaviour and welfare of captive-bred silver foxes housed in groups of different ages was investigated. The study demonstrated that the first weeks of social housing had a considerable effect on the health and welfare of the individuals in the study. Online reports from fox owners correlates this information, with similar behavioural patterns and incidents of poor health seen in pet foxes over the same time periods.

Therefore, it is important to bear in mind the social nature of an individual when deciding keep more than one silver fox. Separate animals that continue displaying aggression towards conspecifics for longer than 2-3 weeks, as well as those that display high instances of agnostic and aggressive behaviours outside of the expected seasonal peaks.

Because initial social contact between silver foxes usually involves agonistic displays as a part of foxes’ social dominance assessments and owing to their territorial motivation, the incidence of serious aggression may put foxes’ welfare at risk. The aim of this study was to investigate the consequences of housing adult silver fox vixens in triplets of various age compositions on their agonistic behaviour, body weight gain and bite injury level following the first hours and days after mixing in triplets... in September.

The triplets were housed in standard wire mesh cages connected with openings and with access to top nest boxes. The foxes’ behaviour was recorded... the number and severity of bite injuries were assessed. There was no overall difference between groups in observed agonistic behaviours. In all experimental groups aggression was most frequent the first hour [chasing; physical aggressive signals; fights]. Overall, number of aggressive interactions was reduced with time... Scabs and/or bite injuries were recorded in 58.3% of the animals the first week and in 42% the second week.

Social grooming and play was only observed at very few occasions. About 35% of the animals, except for controls, lost weight the first week. Vixens with injuries gained less weight compared to unharmed animals... A negative correlation between weight asymmetry and number of fights was found... Although a clear effect of age composition was not found the triplets consisting of 2-year olds might have experienced less negative consequences of group housing because of absence of serious wounds.

Due to the frequency and intensity of aggression and the fact that several vixens lost weight during the first week it is most likely that adult silver fox vixens experience the initial phase of social housing as stressful."

The captive breeding of silver foxes has resulted in both physical and behavioural differences between them and their wild counterparts. These behavioural changes are predominantly focused around human interaction and there is much research on the subject, but there are several studies that have been conducted with captive bred silver foxes, demonstrating their social structure and preferences among conspecifics. A 2007, Norwegian study demonstrated how silver foxes are socially motivated;

"To investigate the strength of social motivation and the motives underlying social contact in farmed silver foxes... we housed six young vixens continuously... and measured their ‘maximum price paid’ when required to perform a task to obtain unrestricted social contact or food.. both test and stimulus foxes could decide their own visit durations to a shared compartment.

Their motives for visiting this ‘social compartment’ were examined by recording their behaviour during social contact. When access was almost free... the test vixens... spent 45% of the time together per 24 h. The stimulus foxes spent on average 80% per 24 h in the shared compartment. When higher costs were imposed, the test vixens proved willing to pay to access the stimulus vixens...

The behaviour recordings showed that during initial encounters the vixens would fight to establish dominance, and in four of the pairs the test subject emerged as the dominant individual. However, during subsequent interactions, no serious aggression was recorded and social behaviour was characterised by higher levels of sniffing and grooming... play signals... and agonistic displays.

Not all of the time together was used for social interaction and during the observation period, the vixens allocated... time to synchronous resting. We conclude that young silver fox vixens were motivated for social contact, and that this contact was beneficial for welfare due to the low level of aggression and the occurrence of grooming and play."

The abstract below, from a study by the Institute of Applied Biotechnology, demonstrates how farmed silver foxes retain the extraterritorial motivations seen in wild red foxes (this dispersion season is known as the 'October Crazies' to captive-bred fox keeper);

"Aggressiveness between family members increased from July until October, leading to a more scattered use of the available space. Furthermore, the mean activity level of family members increased, and the synchrony of activity decreased. We conclude that social tension in the fox families increased gradually during the autumn, leading to dispersion of the family members."

Leena Ahola & Jaakko Mononen, 2001

The Norwegian University of Life Sciences also studied socially housed farmed silver foxes in order determine their social preference at different ages. The study found that newly weaned silver fox cubs were more playful and actively sought company, showing no preference towards familiar or unfamiliar foxes, compared to older animals. Older animals were less concerned about conspecifics and displayed more agonistic behaviours.

"Determining foxes’ social preference, and how this influences their social behaviour towards different conspecifics at different ages may give us a better understanding of how to prevent foxes from exposure of possible social stressors when housed in groups. Here, we investigated the effect of familiarity on social preferences in silver fox females and their motives for seeking social contact at two different ages.

Fourteen silver fox females conducted two preference tests, first at the age of 9 weeks and the second at the age of 24 weeks, where they could choose between an empty cage, a familiar female or an unfamiliar female at their own age. The position and behaviour of the females were recorded using instantaneous sampling every tenth minute for 26 h.

There was a clear preference to seek contact with a conspecific at 9 weeks of age... The cubs did not differentiate between a familiar or unfamiliar stimulus animal... however there was a tendency to play more in front of the unfamiliar stimulus animal... No preference was seen for either the familiar, unfamiliar or empty cage stimulus when the females were 24 weeks old... however they were more aggressive towards the unfamiliar stimulus animal...

Thus, there was no effect of familiarity in time spent with a social stimulus at either age, however these results suggest that the motives for seeking contact as cubs were non-aggressive and possibly play related, whereas the aggressive behaviour displayed by juveniles towards the unfamiliar female indicates an increased competitive motivation"

Agonistic Behaviour

Agonistic behaviour is social behaviour that is related to fighting and the establishment of dominance hierarchy's among animals, it encompasses all of the aggression, appeasement and avoidance behaviours that occurs between members of the same species during social interactions.

The immediate goal of most agonistic behaviour is to establish and maintain dominance hierarchy's between subordinate and dominant foxes with as little conflict as possible. Agonistic interactions can be divided into three types of behaviour; threat, aggression and submission. While these behaviours are interrelated with aggression, they fall outside it's narrow definition; behaviour that is specific in serving to harm or intimidate another (silver foxes have also been domesticated for their aggressive behaviour traits).

Most social agonistic behaviour in captive foxes is seen between competing males, but it may also occur between females, between males and females or between foxes and their human carers. Social aggression increases during adolescence (‘October Crazies’ ) and again during each breeding season (October-March), this is reduced with neutering, especially if done at an early age. More serious cases of aggression is commonly seen between females and around food.

Agonistic behaviour is strung together into sequences that vary in their intensity and duration. The lowest intensity social encounters result in chasing and following, as the intensity increases, posturing and lunging occur, until eventually, physical contact like sparring and biting. These physical encounters may escalate in rare instances into a fight to the death, especially between species (such as that of the Red fox and the Arctic fox), however, Silver foxes are more playful and less aggressive than their wild counterparts.

Types of agonistic behaviour observed in captive bred foxes, as seen in our own observations and recorded in studies (Karl Frafjord, 1993):

- Aggressive neck grooming (Offensive) - Grooming consists of rapid little nibbles in which the fox that is doing the grooming seizes folds of skin between their teeth. The groomed fox remains immobile, any sudden movement may trigger an escalating response from the fox doing the grooming.

- Ignoring (Defensive) - When one fox ignores the advances of another.

- Evading (Defensive) - When one fox takes measures to avoid contact with another.

- Follow (Offensive) - When one fox will walk or run after another.

- Chase away (Offensive) - When one fox will walk or run towards another. Head is frequently lowered and tail is slightly elevated. They may attack the other fox physically and pursue them for a short distance.

- Positioned over (Offensive) - When one fox jumps/stands over, sits on or lies upon another fox.

- Turn away (Defensive) - When one fox turns away from another fox to prevent them from reaching the head and neck region.

- Back arch (Defensive) - Walking slowly on stiff legs, back arched, head slightly lowered.

- Submissive towards (Defensive) - Orientated towards another fox, head is lowered, ears backwards. May remain stationary or move towards the other fox. Tail is somewhat raised and curled to the side.

- Submissive away (Defensive) - Similar to the preceding behaviour but orientated away from the other fox.

- Play mount (Offensive) - Standing upon another fox by clasping their sides with their forelegs in a mounting position.

- Press against (Offensive) - Two foxes lie against each other in a head to tail position, pushing against each other’s bodies often taking a firm hold of each other’s tail in their mouth.

- Rear against (Offensive) - Two foxes balance on their hind legs, stabbing with the forelegs against each others shoulders. Ears are back, mouths are open and teeth are exposed.

- Wresting (Offensive) - Intensive physical contact during play fights, the attack is generally directed toward the scruff and neck.

- Jaw gape (Defensive) - Fox is lay down with it's tail between legs, belly partly exposed. Mouth is open displaying teeth and ears back.

- Lunging (Offensive) - Lunging is directed at another fox. Legs are stiff, head is lowered, ears are back and mouth is open. May involve tail biting.

- Belly roll (Defensive) - One fox will roll over exposing it's belly to the other. Tail moves quickly from side to side as a sign of appeasement.

- Positioned over/Rear against (Offensive) - One fox is positioned over another. Forelegs stabbing against each other. Mouth open, teeth-exposed, ears back.

Many agonistic interactions consist of one fox chasing another for a few seconds. The chased fox flees and either outruns or hides from the pursuer, or sometimes the pursuer desists. If the pursuer catches up, they may nip or bite the rump or tail of the fleeing fox in attempt to engage them in an encounter.

The pursued fox may decided to stand their ground and can turn to face their pursuer, initiating a stand-off. The defending fox may show an open-mouth tooth display, with vocalisation and posturing, and both foxes fur may display piloerection. Frequently, the encounter goes no further, and one of the foxes (usually the pursued one) retreats.

If neither fox flees, the encounter may escalate into physical contact. The foxes may begin sparring, where they raise onto their hind legs, mouth open and teeth exposed which will eventually lead to a full on attack, if neither backs down. Subordinate foxes (especially if young or the foxes are confined to an enclosure), will eventually conceded by rolling over exposing their stomachs as a sign of appeasement, or by fleeing.

Vocalisations & Body Language

"Interpreting the meaning behind canid body language, and subsequently categorizing it, is not a straightforward task because there is a striking, albeit superficial, similarity between domination and play. Indeed, anyone who has witnessed domestic dogs playing together will probably have noticed that the ‘rough and tumble’ can appear quite aggressive to the casual human observer.

While screaming and actions aimed at causing physical injury (i.e. biting, scratching, etc.) are good indicators that the animals are fighting, much body language (gaping, pouncing, erect ears and tail, rolling around together, etc.) appear in playful and aggressive encounters. Moreover, tensions can rise and fall quickly, such that what starts out as a playful encounter could end up an aggressive one."

Wildlife Online, Red Fox Behaviour - Red Fox Body Language, 2023

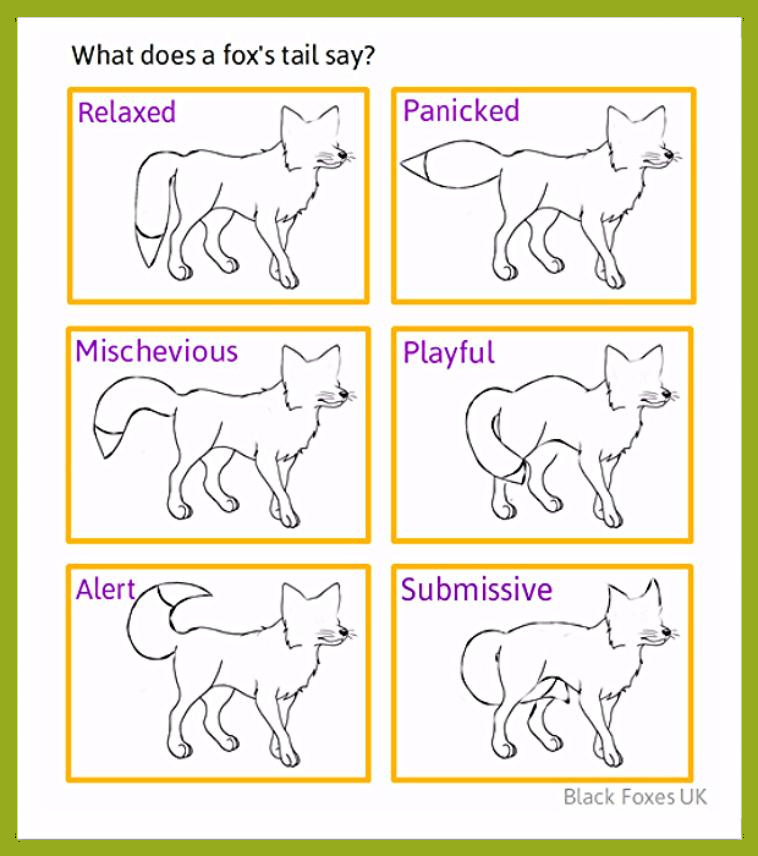

'Tail Speak'

Since silver foxes are such different animals from not only us, but from anything we are used to keeping in captivity, understanding how they communicate isn’t something that comes naturally. It is important that prospective keepers take the time to learn because understanding how foxes communicate helps us to understand them better and allows us to better read their emotions, identifying situations that cause them distress, pleasure or ill health more quickly.

As with other pets, a fox's tail can tell you something about its mood and a wagging tail in a fox is a sign of happiness, just as it is for other canids, such as dogs. However, it is often accompanied with 'screaming laughter' and 'happy wees' (which is far more ingrained that it might be in dogs).

'Airplane Ears'

Foxes display 'Airplane Ears' when they feel threatened, anxious or agitated, as well as when they are play fighting. 'Airplane Ears' are when their large ears flatten and point back, helping to protect the ear drum from unpleasant noises and the ear itself from physical injury. It is an agonistic behaviour and a form of communication that serves to reduce or avoid the chance of injury.

As fear and aggression are both are a part of the 'fight or flight'response they present as very similar behaviours, but there are subtle differences. A fearful fox will move away from the perceived threat wherever possible (flight). An aggressive fox will make moves towards their target (fight).

While play fighting is vital for development, it can be difficult for those that aren't familiar with fox behaviour to tell the difference. With play fighting, the behaviours are often more exaggerated, the animals will willingly make themselves vulnerable and they will continue to go back for more.

'Vixen's Scream'

Fox vocalisations are poorly documented and they can sound spine-chilling when you don't know what they mean. Tembrock (1957) divided them into 28 groups and 40 call types, but his classification was based on captive animals and was mostly subjective, being produced before widespread use of sonographic analysis. Tembrock also noted that foxes have their own unique voice.

"There are individual variants which show up even at birth, as in the croaking sounds of newborn foxes. The length of the barking stanzas of Vulpes differs from one individual to another and stays the same throughout life"

Sonograpic and field data confirmed 20 different call types in wild foxes, (8 of those calls being cub calls), with the 12 adults calls being recorded including; Yell barks, shrieks, ratchet calls, staccato barks, 'Wow-wow' barks, yodels, barks, growls, coughs, screams, yells and whines.

A study in domesticated silver foxes, using sonographic data and behaviour analysis, noted 10 different call types in foxes, 8 of which are used towards humans, including; Whines, moo's, cackle's, growl's, bark's, pant's, snort's and coughs.

"In this study we classify call structures and compare vocalizations toward humans by captive red foxes Vulpes vulpes, artificially selected for behaviour: 25 domesticated, or "Tame" animals, selected for tameness toward people, 25 "Aggressive" animals, selected for aggression toward people, and 25 "Unselected" control foxes, representing the "wild" model of vocal behaviour. In total, 12,964 calls were classified visually from spectrograms into five voiced (tonal) (whine, moo, cackle, growl and bark), and three unvoiced, or noisy (pant, snort and cough) call types. The classification results were verified with discriminant function analysis (DFA) and randomization.

We found that the Aggressive and Unselected foxes produced the same call type sets toward humans, whereas the Tame foxes used distinctive vocalizations toward humans. The Tame and Aggressive foxes had significantly higher percentages of time spent vocalizing than the Unselected, in support of Cohen & Fox (1976) hypothesis that domestication relaxes the selection pressure for silence, still acting in wild canids. Unlike in dogs, the "domesticated" Tame foxes did not show hypertrophied barking toward humans, using instead the cackle and pant. We conclude that the use of a certain call type for communication between humans and canids is species-specific, and not is the direct effect of domestication per se."

Domestication influences the behavioral and vocal responses of foxes bred and raised around humans, creating an adapted behavioural response specifically for attract human attention and communicating excited, positive emotions.

"Silver foxes of Tame strain, experimentally domesticated for a few tenses of generation, displayed bursts of vocal activity during the first minute after appearance of an unfamiliar human, that faded quickly during the remaining time of the test, when the experimenter stayed passively before the cage.

Distinctively, foxes of Aggressive strain, artificially selected for tenses of generation for aggressive behavior toward humans, and the control group of Unselected for behavior silver foxes kept steady levels of vocal activity for the duration of the tests. We found also that Aggressive foxes vocalized for a larger proportion of time than Unselected foxes for all 5 min of the test.

We discuss the obtained data in relation to proposal effects of domestication on mechanisms directed to involving people into human-animal interactions and structural similarity between human laughter and vocalization of Tame foxes."

However, the study also shows that while humans are good at identifying negative emotions, we are not so good at identifying positive emotions in foxes;

"Research shows that humans identify emotional arousal in vocalizations across multiple species, such as cats, dogs and piglets. However, no previous study has addressed humans’ ability to identify emotional arousal in silver foxes.

Here, we adopted low and high arousal calls emitted by three strains of silver fox - Tame, Aggressive and Unselected - in response to human approach. Tame and Aggressive foxes are genetically selected for friendly and attacking behaviors toward humans, respectively. Unselected foxes show aggressive and fearful behaviors toward humans.

These three strains show similar levels of emotional arousal, but different levels of emotional valence in relation to humans. This emotional information is reflected in the acoustic features of the calls... Our data suggest that humans can identify high arousal calls of Aggressive and Unselected foxes, but not of Tame foxes"

'The Happiest Fox'

Not only do foxes 'laugh' when they are really excited, but they also 'smile' too!

It is true that foxes lack the facial muscles to smile like we do, drawing our lips back and up (they also lack the facial muscles to snarl), but a happy 'smiling' fox can be identified by the calm, positive energy it radiates. As with humans, calm animals are more alert and accepting to the world around them, which shows in the brightness of their eyes and through their forward, alert ears. Animals in a state of calm may also relax their jaws, giving the impression they are smiling.

"Until recently, most animal behaviorists believed that an animal’s use of what we call a smile is no more than a collection of conditioned reflexes that move the muscles in the face. But new thinking on the subject is now allowing for the possibility that animals are expressing happiness when they 'smile'."

Do Animals Smile? | Ecology Global Network, 2019

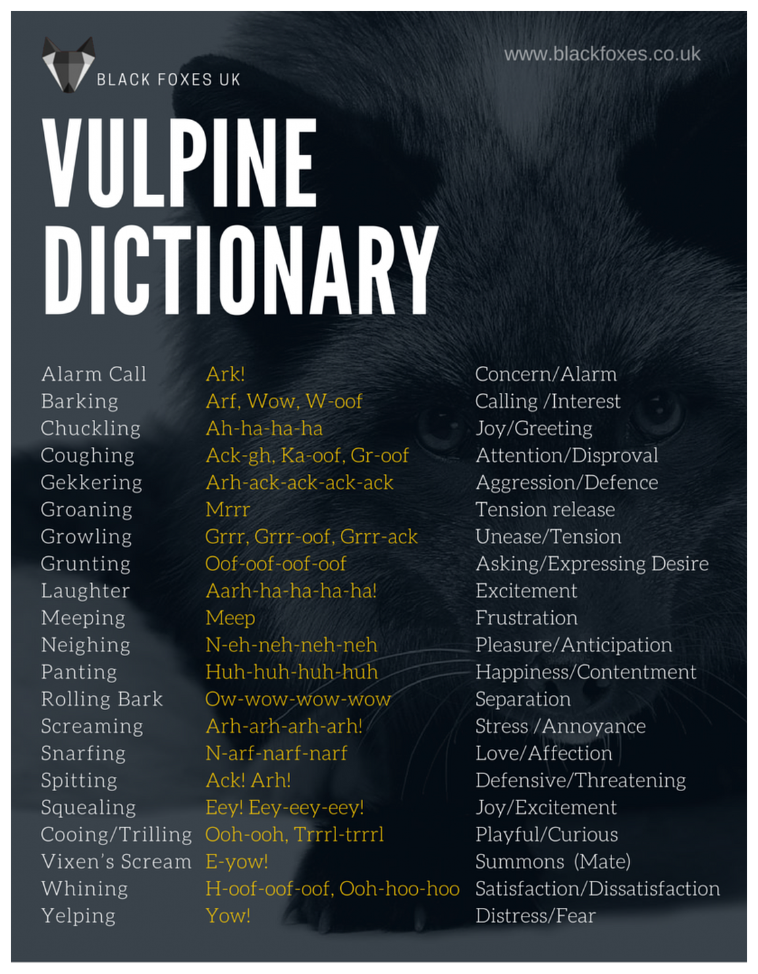

Knowing how difficult it is to understand foxes and in order to assist new keepers in identifying what it is their fox is trying to communicate, we created a 'vulpine dictionary' to help overcome the communication barrier. Have you ever heard these sounds before, what did you think?