Frequently Asked Questions

What is a silver fox?

Are silver foxes domesticated?

What colours are UK foxes?

What do I do if I find a lost pet fox?

What do I do if a wild fox is approaching?

What do I do if a fox is sick or injured?

What do I do if I find a fox cub?

How do I deter foxes?

Are cats safe around foxes?

Why do foxes smell so bad?

What are the 'October Crazies'?

Was That A Fox?

If you are unsure if you saw a fox or not, please contact us to detail the sighting and we will help you identify the animal in question. If possible, take footage of the animal for a more accurate assessment.

More often than not, people see an unusual fox and need clarification that this is indeed what they saw, such an encounter is often the first time someone has learnt of these animals. Most of the reports made to Black Foxes UK over the years have been confirmed as melanistic or unusually coloured foxes and a correct assessment was made by those who saw the animal, however unusual the occurrence.

On several occasions, those reporting an unusual fox have mentioned they had originally thought they had seen a 'big cat', until they discovered melanistic and silver foxes existed. On two occasions, lost and foxy-looking dogs have been mistaken for melanistic foxes, however this is a relatively small number considering the amount of reports we receive (300-400/year, between 2015-2023). A large portion of these reports are of missing exotic pets, such reports are received in much greater number than for wild fox reports and is one of the indicating factors the fox in question might be an escapee. One trend noticed in our reports over time, is that we now receive more wild fox reports and the incidence of escapees reported has reduced.

To send footage or photos for identification, please email blackfoxesuk@gmail.com.

What Is A Silver Fox?

Put simply, the 'silver fox' is the name given to the 'domesticated North American red fox'. In order to avoid confusion between missing pets and wild foxes, we use the term 'black fox' to describe the melanistic red foxes that are wild in the UK and the term 'silver fox' to describe captive-bred foxes.

You could say, "wild boar are to pigs, what the red fox is to the silver fox" and in the same way wild boar and red foxes have a restricted colour range, farmed pigs and silver foxes have a much greater variation of patterns and colours.

The North American red fox is found in Canada and North America and is a species that was once farmed here for its fur and is now kept as an exotic pet or within animal collections. It was originally classified as 'vulpes fulva' which can be divided into 12 subspecies and which occur naturally in 3 statistically predictable colour variations (red, cross and silver).

The North American red fox was the source supply for the development of the 'farmed silver fox', a captive-bred fox that has been selectively bred since the 1800's and was domesticated for its fur traits, existing in over 70 different colour variations today. The development of the fur trade and the 'silver fox' was termed 'the silver rush' and had a significant impact on society around the world.

In 1959, the North American red fox was reclassified as 'vulpes vulpes' and deemed invasive in the US, due to the incorrect assumption that the farmed foxes were imported from Europe by European settlers and that it was their escaped descendants that were spreading across the US. The move allowed for their persecution in the wild and the continued free movement of silver foxes around European fur farms.

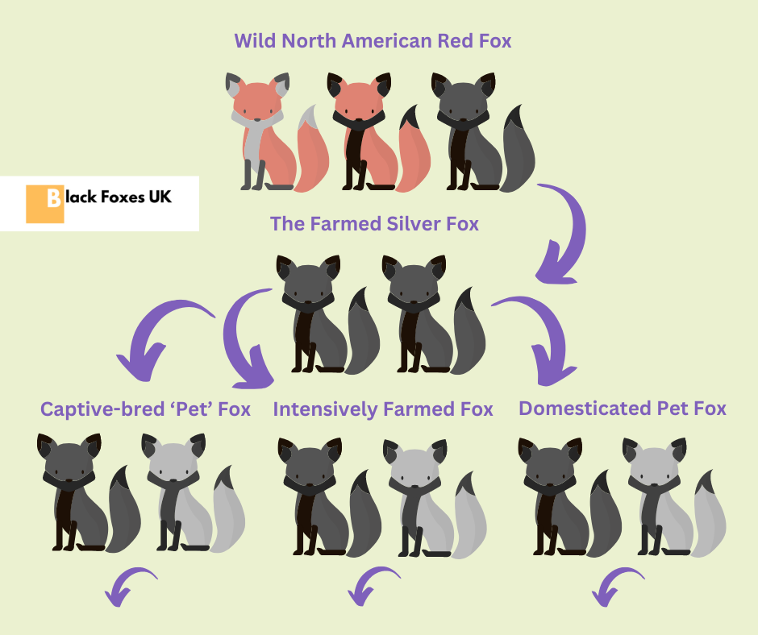

Today, silver foxes exist in at least 2 distinct lineages or 'breeds' (with their own governing bodies and associations that regulate breeding), as well as a lineage or 'breed' maintained as exotic pets;

- The Farmed Silver Fox - An intensively farmed 'working line'

- The Captive-Bred Silver Fox - An exotic pet 'companion animal line'

- The Russian Domesticated Red Fox - The scientifically domesticated 'show line'

Their complicated history and mis-classification makes it difficult to manage them correctly under legal frameworks in the UK but it is a complex and unusual situation and not one science and law are going to agree upon any time soon. It doesn't help with the confusion that their names are based on colour!

You can learn more about the history of the silver fox by heading to our information page.

Are silver foxes domesticated?

As the Phys.org article states, yes, all silver foxes have been domesticated to some extent. Domestication is a complex process with varying goals and outcomes, depending on the traits selected—whether physical traits, like fur quality, or behavioral traits, like tameness or aggression. This distinction is important because domesticated animals vary greatly depending on whether they’re bred for production, as farm animals, or companionship, like pets.

The domestication process involves gradual behavioral and genetic changes to help animals adapt to living with humans. However, tracing the early domestication stages is challenging, as most domesticated animals have been raised in captivity for so long that the transition from wild to tame has become difficult to study. Silver foxes, though, are a rare exception, as their breeding was carefully documented starting in the late 1800s.

Silver foxes were first bred for fur in captivity on Canada’s Prince Edward Island in 1896, with their lineage later spreading globally and intermixing with some wild populations, which may explain unique genetic markers seen in some wild populations. After World War II, North American fox farming declined, while Eurasian farms, bolstered by government support, maintained greater genetic diversity.

The study also examined the famous Russian Farm Fox experiment, begun in 1959 in Novosibirsk. Starting with the least avoidant foxes, scientists selectively bred them over generations for tameness, eventually producing foxes as friendly as dogs. Genetic analysis, however, found no unique origins in these foxes, suggesting that the potential for friendly behavior is widely present in all captive-bred silver foxes lineages, and can be encouraged through specific selection pressures.

What Colours Are UK Foxes?

The fox population in the UK is predominantly red, with the characteristic white-tipped tail, often called a brush. According to Memoirs of British Quadrupeds, and historical naturalists, three distinct types of foxes were once recognised:

- The Highland Fox or 'Greyhound Fox'

- The Lowland Fox or 'Cur Fox'

- The Urban Fox or 'Mastiff Fox'

These classifications were based on their physical characteristics and the environments they inhabited. The Highland Fox, commonly known as the 'Greyhound Fox' or 'Mountain Fox' is now considered extinct, and was the largest of the three. It had a predominantly grey coat and was well-suited to hilly terrains. The Lowland Fox, known as the 'Cur Fox' or 'Corgi Fox', was smaller and more widespread, inhabiting lowland areas. It was distinguished by its bushier tail, which was sometimes tipped with black. The Urban Fox, referred to as the 'Mastiff Fox' or 'Bulldog Fox', was the most robust in build. It was reported to be built for strength rather than speed, with a broader head, a coat that could occasionally be flecked with white, an occasional black belly, and a tail tip that could also be black.

Interestingly, a study conducted in the UK in 1963 showed that in England & Wales, 22% of foxes had a black or absent tail tip and that in Scotland, 13% had black or absent tail tips. The remaining foxes had the distinguishing white tail tip.

Due to over-hunting, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries, foxes were imported from continental Europe to replenish dwindling populations. By the late 19th century, North American red foxes were also imported for the fur trade. Today, the UK fox population is likely a genetic blend of these imported foxes, escaped fur-farm foxes, and the few remaining native ones, resulting in a diverse genetic admixture.

While the majority of UK foxes are still red, sightings of foxes with unusual colour variations have increased significantly in recent decades. These include:

- 'Black bellied' mutations

- 'Black brush' mutations

- Fully melanistic - black and silver mutations

- Partially melanistic - smokey mutations, cross mutations, diluted silver cross mutations, silver cross mutations and other partially melanistic mutations.

- White and leucistic mutations

- Red and silver platinum mutations

- Whitemark mutations

- Ringneck mutations

- White brush mutations

- Red and silver white spotted mutations

- Black spotted mutations

- Striped mutations

- Brown mutations

- Colour changing mutations

- We also see dwarf mutations

Historically, colour anomalies such as 'black-bellied' or 'black brush' foxes were rare, with fully melanistic or leucistic foxes reported only a few times per decade. Since 2000, however, sightings of melanistic (black or partially black), leucistic, and white-spotted foxes have surged, with Black Foxes UK receiving 300-400 reports annually between 2015 and 2023.

This rise in colour variation is thought to be influenced by crossbreeding with non-native foxes, particularly escaped North American red foxes, contributing to increased genetic diversity in wild populations. Though red foxes remain the most common, these atypical colourations are now more frequently observed, especially in areas with known mutations present, something we attribute to topography and closed breeding populations.

What Do I Do If I Find A Lost Pet Fox?

Do not record any fox known to be an escaped captive-bred silver fox onto the biological records system. Recording missing exotic pets onto such a system may negatively influence results (due to the sheer amount of reports that often occurs with known escapees).

Captive-bred silver foxes can often be identified by their larger size, longer fuller coats, a larger white tail tip, their unusual behaviour and by their unusual colours or patterns (though this is not always the case; red morph silver foxes are also kept and bred in captivity and many melanistic and unusually coloured foxes exist in the wild in the UK today).

If you believe you have seen an escaped pet or are unsure if the fox you saw was wild or captive-bred, make a note of the time and location, take footage if you are able and contact us for identification and further advice. If it is known the fox is an abandoned captive-bred silver fox escapee, you may also be advised to contact the RSPCA.

Please be aware that the RSPCA and other animal or wildlife rescues may not always act to recapture abandoned captive-bred silver foxes unless the animal is injured or causing a nuisance in a public place. This is because the species status of both captive-bred silver foxes and wild native foxes is 'vulpes vulpes' and there is legislation that details how they can be managed, differing if they are wild or captive-bred. If a keeper does not come forward to confirm captive-bred status, because they can be difficult to distinguish from native wild foxes, animal and wildlife rescues may only be able to attend when policy dictates.

The process of accurately identifying captive-bred silver foxes, safely capturing them and providing them with secure housing, is a complex undertaking that demands significant time, planning, collaboration and resources to arrange. While we will always strive to ensure escaped captive-bred silver foxes get the help they need, it is important to note, we are not an animal capture organisation nor an animal rescue, despite our aspirations, assisting escaped silver foxes is an informal response to a need on our part.

What Do I Do If A Wild Fox Is Approaching?

Do not feed approaching foxes, this will only reinforce the behaviour and once habituated, they may visit strangers to test their new skills.

It is common to see foxes out during the day and in urban areas, especially over breeding and cubbing seasons. They may get unusually close at times however, they should run away if you approach them or make a loud noise, due to their natural fear of people.

If the fox does not run away, it is often due to a conditioned association of people with food. Foxes are not dangerous to humans, but small pets like rabbits or chickens may be viewed as prey and an overly habituated fox may nip at clothing in order to elicit a feeding response.

A wild fox in general, should not be approaching people and doing so may be a sign they are sick and in need of veterinary assistance (e.g. toxoplasmosis), it could also mean that they were rehabilitated and released recently or it could mean they are a missing captive-bred fox.

If you are concerned about an overly bold fox, please use our links page, to locate a trained wildlife specialist or rescue for further support or contact us for identification.

What Do I Do If A Fox Is Sick Or Injured?

If you find an injured fox, do not approach it without the guidance of a wildlife specialist. Make a note of the location and contact a wildlife rescue that can provide advice, signposting or assistance.

Do not approach, handle or distress the fox, which might cause it to run away or injury itself further. While very unlikely, it is also important to note that humans can potentially contract certain illnesses from foxes including mange and bird flu, so it is best to seek advice in advance of assisting the animal. Do not seek veterinary advice off of strangers on social media, ensure you consult a specialist directly.

Sarcoptic and Dermodedic mange or 'mange', are the most common conditions encountered in foxes. Clinical signs of mange are hair loss, thick crusting and intense itchiness. The infection is caused by 2 different varieties of mite, which are not deadly, but foxes suffering from manage are at risk of a number of infections and if left untreated starvation and organ failure may occur. It is important to remember that nature has its own balance and for a fox to remain healthy and thrive, they require a healthy environment and the right plants to do that.

Mange has a similar in presentation to seasonal moulting in foxes, which for the silver fox especially, can leave them looking rather 'dog-eared' during these times, with people often confusing the presentation for them being malnourished and mange ridden. A fox in moult does not require any treatment or assistance.

The best course of action when you are concerned about a wild fox is to contact a trained wildlife specialist or rescue. Please use our links page, for further support.

What Do I Do If I Find A Fox Cub?

Do not try to feed, move, handle or approach the fox. Make a note of the location and contact a wildlife specialist immediately.

It is not unusual for cubs to be left alone while the parents hunt, but if you have reason to believe that the parents have been killed or the cub is in distress, be sure to let the rescuers know. Do not take on the responsibility of raising a wild fox yourself, unless provided with specialist wildlife support.

Raising a wild fox incorrectly robs them of the possible opportunity to be returned to the wild. Once fox cubs reach maturity, they are very difficult to live with and a lot of resources and specialist equipment is required. It is around this age, those who rescue wild fox cubs seek the correct help but by this time, it is often to late to acclimatise the fox for release.

The best course of action when you are concerned about any wild fox is to contact a trained wildlife specialist or rescue. Please use our links page, for further support.

How Do I Deter Foxes?

During springtime when foxes are preparing to raise its cubs, you may find they make a home of your garden. Consider allowing the family to remain until the cubs are old enough to leave the den with the parents (about 6-8 weeks old).

Fox families fully disperse come autumn, ready for mating season over late winter. Once the fox family has vacated, you can block up the entrances, which will prevent them from using the same spot in future.

If you need to remove foxes from a site you can read our fox deterrent article or you can locate a wildlife specialist or rescue on our links page, for more information and support. Alternatively, you can contact a humane fox control expert, who will be skilled at swiftly protecting homes, work places, schools and other establishments from encroaching foxes, without causing them any harm.

Are Cats Safe Around Foxes?

While it’s a common concern, the idea that foxes pose a significant danger to cats is largely a myth. Foxes and cats share many similarities, as both are territorial and opportunistic hunters that compete for similar resources, such as small mammals and birds. However, foxes do not prey on cats, and in most cases, the two animals will avoid confrontation. Incidents of aggression between foxes and cats are rare and usually accidental or the result of territorial disputes, much like what happens in interactions between cats or other animals. Due to their size, foxes are more likely to unintentionally injure cats in such encounters rather than deliberately attack them.

Interestingly, the red fox is the only known mammal to naturally produce a chemical compound similar to catnip. This compound, found in fox urine, can trigger a calming response in some cats, possibly explaining why foxes and cats often coexist peacefully in urban environments. The presence of this compound might even be an adaptive trait that has helped urban foxes live alongside domestic cats with minimal conflict. While cats should always be monitored when outdoors, the risk of harm from foxes is generally very low and often accidental.

Why do foxes smell so bad?

Foxes are well-known for their strong, musky odour, which comes from a variety of specialised scent glands located across their bodies. The most prominent glands are around their tail and anus, but they also have scent glands on their paws and faces. These glands play a crucial role in fox communication, as the scent they release is used to mark territory, signal dominance, and communicate with other foxes. By rubbing their faces or scratching surfaces with their paws, foxes leave their scent behind, creating a "scent map" that helps them navigate their environment and alert others to their presence. The persistent nature of their scent allows these markings to remain effective over time, ensuring that their messages to other animals are clear.

The powerful scent produced by foxes is not just for marking territory but also for signalling their presence to other foxes, predators, or potential mates. The odour can even be strong enough to cause evacuations, and the oily secretions from their glands permeate everything they touch. Foxes have specialized scent glands that produce an oily secretion, which is designed to cling to surfaces and remain effective over time. These oils create a strong bond with various materials, including fabrics and porous surfaces, making the scent challenging to wash away with standard cleaning methods.

The chemical composition of fox scent further contributes to its persistence. The odour comprises a complex mixture of volatile organic compounds, including fatty acids and sulfur compounds, which have strong adhesive properties. These compounds bind tightly to surfaces, and their complex nature means that conventional cleaning agents often fail to fully break down or eliminate the scent. Additionally, the natural persistence of the scent compounds means that even after cleaning, residual odour can linger. The oils and chemicals continue to emit their characteristic smell, requiring specialised cleaning products or treatments designed to address oil-based residues. As a result, fox scent can remain detectable for extended periods, presenting a significant challenge for complete removal.

What are the 'October Crazies'?

The term "October Crazies" describes a noticeable change in fox behaviour that occurs annually during the dispersal season. Fox owners often see an uptick in restless, sometimes erratic behaviour from late summer through to autumn, particularly among young foxes in their first year. This period is linked to the natural cycle of fox maturation, when young individuals begin to experience hormonal shifts as they prepare for independence, which has an impact on them and their adult conspecifics. The signs of this phase can include increased energy, more scattered movement patterns, and even bouts of aggression.

Historically, it was believed that this behaviour stemmed from the fox’s transition into maturity, much like the teenage years in human development. Foxes become less reliant on their family units during this time, seeking out their own space in what seems to be a natural drive for independence. This shift has led to the common recommendation that foxes, especially during this season, be given additional space to accommodate their changing needs.

Recent research has provided a scientific basis for what fox owners have long observed. A 2002 study on farmed silver foxes found that as the dispersal season progressed, family units experienced increased social tension, with rising levels of aggression and declining synchrony in behaviour. Foxes began to move more individually within their enclosures, reflecting their need for space and independence. The study concluded that this behavioural shift is a natural part of fox development, confirming that the "October Crazies" are linked to the dispersal process and hormonal changes, as foxes prepare to establish their own territories.