Routine Health Care

Routine health care is an important part of pet ownership. Animals are adept a hiding signs of injury or illness and foxes are no different. Less is known on the health and behaviour of captive foxes compared to other pets, so it is extra important they are checked daily for signs of ill-health.

Before bringing a fox home you should ensure there is an Exotic Pet Vet willing to register you and your specialist pet. Book an appointment for an initial health check as soon as you get home, and make arrangements for any vaccinations, parasite protocols and treatments the vet may recommend.

Training your fox to tolerate handling from a young age will not only help to secure the bond between you and your fox, but it will also aid you in conducting thorough daily health checks, which will help you build an understanding of what is "normal" for your particular fox.

It is important to remember that a fox's environment and emotional well-being are interconnected with their health and behaviour. A suitable diet, enclosure and plenty of species specific enrichment go a long way to ensuring your pet remains healthy!

Vaccinations For Foxes

Vaccination safeguards you, your fox and any other pets in the household from nasty diseases that can cause pain and suffering and in some cases, even death. It is important to note that there are not always treatments available, where treatments are available, they can be expensive and in some circumstances even prove unsuccessful. It is for this reason that preventing disease through vaccination is strongly advised.

Vaccinations are given at intervals over specific time-frames, which vary depending on the vaccine in question. They contain a modified form of the virus or bacterium that causes a particular disease and work by stimulating the body's immune system in a safe way. Should your fox come into contact with a disease, the immune system 'remembers the vaccine' and is stimulated into fighting off the disease before it can take hold.

In order for vaccines to provide protection, it is advised that they are given before the animal is allowed to socialise with animals from outside of the home. The ability to socialise with other animals from a young age is essential for the normal social development of a young fox, so for this reason it is vital they are vaccinated as soon as possible.

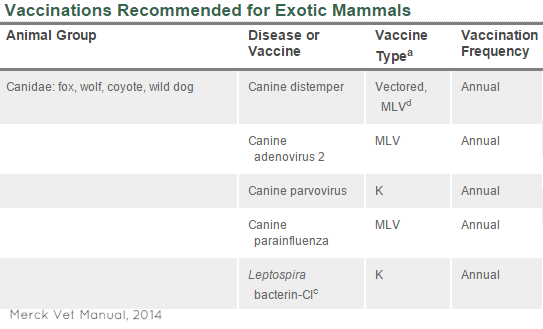

Vaccinations recommended for captive foxes in the UK include:

- Canine Distemper

- Canine Infectious Hepatitis

- Canine Parvovirus

- Leptospirosis

Note: Lyme Disease and Canine Influenza Virus vaccines are now available for dogs in the UK. It is not yet clear if these are suitable (or recommended) for use in pet foxes.

How The Silver Fox Helped Reduce Disease:

The canine distemper vaccine still used in pets today was originally developed by a U.S. fox farm in the 1930's and has been helping to protect pets from this disease since.

"Research on the once-world’s-largest fox farm, completed by Dr. R. G. Green in 1938 while employed under the Fromm Bros. in the Fromm Laboratory, is the reason dog and ferret owners have access to the distemper vaccine today"

US Fox Shippers Council - The Invention of the Fromm-D Distemper Vaccine

Parasite Treatment For Foxes

Captive foxes, like other pets, require regular treatments to help prevent them from suffering parasite problems. Your exotics vet will be able to provide advice about what products to use, how effective they are, and how often to use them.

Parasites such as worms, ticks, fleas and mites present a disease risk to both humans and animals, so it is important not to look over this aspect of health care. Ticks and fleas are known to carry many different pathogens and can easily transmit disease between wild animals, domestic pets and humans, if these pests are not kept not kept in check.

To keep parasite burdens down ensure you stick to a regular parasite schedule, that bowls, bedding and litter boxes are kept clean. Remove and unwanted leaf litter from enclosures, keep weeds and plants trimmed back and ensure cats and rodents cannot enter your fox's enclosure. "Deep Clean" your home and animal enclosure once a week and check your pet daily for ticks, fleas and other parasites.

If you find your fox is suffering either internal or external parasites, it is important to seek veterinary advice. Remember to treat not only the animal, but other pets in the home, the animals enclosure and bedding, and your home (should your fox have access). Your vet will be able to recommend products that are safe and effective to use.

Suggested Veterinary Treatment Schedule:

- The prevention of flea, tick and mite infestations often requires monthly control measures. Veterinary products that control such parasites include Stronghold, Frontline, Advantage, Advantage II, Advantix and Effipro. Seresto collars can also be used, lasting 8 months.

- Worming is suggested every three months and should cover roundworm, hookworm, tapeworm, whipworm, heartworm and lungworm. Veterinary products that control such parasites include Drontal, Droncit, Milbemax, Prazitel Plus+, Advocate or Panacur.

- For the home and enclosure, veterinary products such as Indorex can be used. 1 application provides up to 1 year of protection.

For more information, visit the articles:

Grooming & Daily Health Checks

Grooming is not only important for maintaining and assessing health, but the process of allogrooming is an important social behaviour for foxes, contributing to both their physical and mental well-being. Silver foxes will naturally engage in allogrooming of their human carers and other pets in the home, if a strong enough bond develops. Training a fox to tolerate grooming and health checks, ensures you can create a good foundation for a strong social relationship to develop.

Like wild foxes, silver foxes go through a moulting season each year. Silver foxes were originally bred for the fur trade and have developed much thicker and fluffier coats as a result of the selective breeding, which can be a handful when it comes out in a moult, I recommend investing in a good brush, both for the fox and your floor! Alternatively, hand-plucking the moulting clumps of fur can be just as effective.

Seasonal Moulting Behaviour:

Microchipping

Microhipping is now a legal requirement for dogs in the UK. While foxes are canids, they are not covered by this legislation. However, it is advised that you get your fox microchipped at their first health check. This means that should your fox get lost or stolen, it can be identified and you can be notified.

While microchipping is helpful in reuniting lost pets with their owners, details must be kept updated for it to be effective, so remember to keep your details up to date.

Neutering Foxes

"It's Nicer to Neuter!"

Dogs Trust Campaign Slogan

Here at Black Foxes UK we agree. Twice a year, during breeding season and again when young cubs leave their home territory to claim their own, foxes undergo seasonal behavioural changes and become much more challenging. During these times the dynamics of their social alliances changes, they become much more confrontational and are much more likely to attempt to escape.

Young foxes can be neutered from around 4-8 months and should preferably be done before sexual maturity begins at about 10 months. Neutering may help to reduce unwanted behaviours and can also help to reduce not only how strong your fox smells, but the strength and frequency of territorial marking. As with female dogs, it is advise to wait 12 weeks from a season to neuter foxes (foxes are in season for only 3 days of the year, during breeding season).

Neutering also prevents unwanted and unplanned pregnancies and reduces the burden on exotic pet rescues. Most importantly of all, it ensures your pet fox's genes don't end up in the wild fox gene pool.

The Five Freedoms

Everyone responsible for an animal in captivity must comply with the Animal Welfare Act 2006. The act states five needs that owners must ensure they meet. Breech of the Act can result in a fine, imprisonment and/or a ban from keeping animals.

1) The need for a suitable environment - Make sure you fox has somewhere suitable to live. Foxes require a secure enclosure with a minimum of a 100 square foot per fox. While there is no regulation on the size of enclosure anything less than this would not be considered suitable in meeting their needs. The enclosure must include several warm safe places to hide from view and bad weather, it must be escape-proof and it must be safe.

2) The need for a suitable diet - While foxes are carnivores, they are more accurately described as mesocarnivores (animals that consume 50-70% meat). The diet of a captive fox should include whole small prey items daily where possible. Other food items, such as; raw or cooked meat, fresh fruits and vegetables or complete commercial diets can be added to this to provide a balanced and nutritious diet. Do not feed anything that cannot be fed to dogs or cats. Foxes require a higher amount of taurine than dogs but less than cats. A balanced diet, complete with raw meat and whole prey items, will supply your fox's needs.

3) The need to exhibit normal behaviour patterns - Foxes have several natural behaviours that owners can easily accommodate. They are avid diggers, they also bury excess food in a behaviour known as "caching". Providing an area where your fox can dig safely will allow it to display these natural behaviours. Foxes are also great climbers and they enjoy taking in a view from a height, ensure your fox has platforms and climbing branches in their enclosure to allow them to behave as foxes need to behave. In the wild, foxes have to work hard for their food, so make sure you add food enrichment devices to your daily routine.

4) The need to be housed with, or apart from, other animals - Foxes are social animals, but they have a socially select nature which they manage and maintain through agonistic displays. The social life of foxes adapts and changes over time and while some prefer the company of others, some do not. It is important to monitor the social behaviour of foxes that are group housed for this reason, especially during breeding and weaning season. As with the case with cats, there is no welfare concern housing foxes singularly.

5) The need to be protected from pain, suffering, injury and disease - It is your duty as an owner to ensure your fox and it's environment remains healthy. Ensure you are familiar with the signs of normal health and behaviour, if you notice anything out of the ordinary, do not hesitate to take action and contact your vet. Veterinary fee's can be expensive and there is little option for pet insurance for foxes, so ensure you are able to afford any costs that may occur over the course of your foxes life.

Signs of Ill-health in Silver Foxes

- Sickness or diarrhea

- Abnormal weight gain or loss

- Loss or increase in appetite

- Drinking abnormal amounts

- Lethargy or increase in sleeping

- Unusual sores or swellings

- Increase or decrease in toileting

- Limping or weakness on limbs

- Coughing, wheezing or sneezing

- Bleeding

- Scratching or chewing

- Signs of pain (sensitivity)

- Runny eyes or nose

- Changes in behaviour

If you notice any of the symptoms above in your fox do not hesitate to contact your vet.

Ailments of Red Foxes

Captive foxes are just as susceptible to illness and injury as their wild counterparts and keepers need to be aware of the prevalence, transmission and zoonotic potential of diseases in both wild foxes and domestic pets in order to keep their foxes protected. If you think your fox is unwell, seek veterinary assistance.

Important diseases to note among foxes in the UK:

Fox Encephalitis (Adenovirus)

Fox Encephalitis caused by Adenovirus is a viral infection that primarily affects foxes, leading to inflammation of the brain. This disease can have severe neurological consequences and is highly contagious among fox populations. The adenovirus responsible for this condition is capable of causing similar encephalitic symptoms in other wild canids and, in some cases, domestic dogs. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Fox Encephalitis is crucial for wildlife veterinarians, conservationists, and pet owners.

Historically, fox encephalitis been considered 'a common disease of the silver or red fox in captivity' and is readily transmissible between foxes, dogs and other similar animals. Although the agent of the disease was unknown at the time of it's discovery, there was an understanding of a link between fox encephalitis and both distemper and the hepatitis virus'.

The fox encephalitis virus (or canine infectious hepatitis in dogs), is a highly contagious adenovirus, of which there are two strains; canine adenovirus type 1 or adenovirus type 2 (CAV-1 or CAV2). CAV-1 is the strain of most concern in the UK.

The virus invades the endothelial tissues, particularly the smaller blood vessels which results in local hemorrhaging and tissue damage at the affected site. This in turn, leads to inflammation of the brain and other organs.

"ICH was first identified in North America in silver foxes in 1925 (Green 1925), but the disease was only described in domestic dogs in 1947 (Rubarth 1947). Beside red and grey foxes, and other Canidae, such as coyotes, jackals and wolves, CAdV-1 can also infect members of the families... Mustelidae (skunks and otters) and Procyonidae (raccoons) (Spencer et al. 1999)."

As stated by the Merck Veterinary Manual;

"Infectious canine hepatitis (ICH) is a worldwide, contagious disease of dogs with signs that vary from a slight fever and congestion of the mucous membranes to severe depression, marked leukopenia, and coagulation disorders. It also is seen in foxes"

Overview of Canine Infectious Hepatitis - Revised June 2013 by Kate E. Creevy, DVM, MS, DACVIM

A case study of three wild foxes from the UK found that;

"Canine adenovirus type 1 (CAV-1) was isolated from all three foxes. In a serological study, antibodies to CAV-1 were detected in tissue fluid extracts taken from 11 of 58 (19 per cent) frozen red fox carcases from England and Scotland."

Transmission

Animals become infected though contact with contaminated body fluids, urine or faeces, or by breathing in the virus following contact with an infected animal . The virus can be shed in urine for up to a year after the initial infection, posing a risk to susceptible animals who come into contact with it. Contaminated enclosures, toys and bedding etc., can also serve as a source of transmission.

"The virus can be found in the brain, blood, spleen, upper respiratory tract and spinal cord. The reason the virus becomes pathogenic when large groups of foxes are put together is not positively known. Direct contact from quarrelling and the cannibalistic tendency of a fox, are thought to be causes as well as eating and drinking from the same containers.

The portals of entry are the respiratory tract, digestive tract. and skin wounds. Adult foxes (over one year old) are twice as resistant as are the younger foxes. When the disease occurs in a large group of mixed-aged foxes. the mortality rate is about 15-20 percent. Experimental inoculation shows about 80 percent mortality in foxes below the age of 6 months and approximately 15-20 percent mortality in adult foxes."

Clinical Signs

Symptoms of Fox Encephalitis include a range of neurological disturbances. Infected foxes may exhibit behavioral changes such as aggression, disorientation, and lack of fear towards humans. Physical symptoms can include seizures, head tilting, loss of coordination, and paralysis. Other signs include excessive salivation, difficulty swallowing, and abnormal vocalizations. In severe cases, the disease can lead to coma and death. The progression of symptoms can vary, but the rapid onset of severe neurological signs often necessitates swift veterinary intervention.

Hepatitis (CAV-1)

- Partial anorexia

- Hyper-excitability

- Fever

- Vomiting and/or diarrhoea

- Convulsions

- Ataxia

- Weakness of limbs and/or paralysis

- Hallucination

Respiratory Disease (CAV-2)

- Dry, hacking cough

- Retching Coughing up white foamy discharge

- Conjunctivitis

Unusual Symptoms

Blue Eye: A condition caused by corneal clouding (“blue eye”) is the result of immune-complex reactions after recovery from acute or sub-clinical disease. This reaction is also observed in some animals vaccinated with the live attenuated vaccine.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Fox Encephalitis involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and a detailed history of the animal's symptoms and potential exposure to other infected animals. Laboratory confirmation is achieved through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to detect adenovirus DNA in tissue samples, particularly brain tissue. Blood tests and cerebrospinal fluid analysis can also provide supportive diagnostic information. Imaging studies like MRI or CT scans might be used to observe brain inflammation and rule out other potential causes of the symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment for Fox Encephalitis primarily focuses on supportive care, as there is no specific antiviral therapy for adenovirus in foxes. Supportive care may include intravenous fluids, anticonvulsants to manage seizures, and anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce brain swelling. Nutritional support and maintaining hydration are also crucial. In some cases, broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered to prevent secondary bacterial infections. Unfortunately, the prognosis for foxes with severe neurological symptoms is often poor, and euthanasia may be considered to prevent further suffering.

Prevention

Preventing fox encephalitis involves a multi-pronged approach focusing on reducing exposure to causative agents and enhancing the overall health and resilience of fox populations. Key measures include controlling vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks, which are common carriers of encephalitis-causing viruses. Implementing habitat management strategies to reduce vector breeding sites, such as standing water, can significantly lower the risk of transmission.

Monitoring fox populations for signs of encephalitis and conducting regular health assessments can facilitate early detection and prompt response to potential outbreaks. Public education plays a critical role in prevention. Raising awareness among communities about the importance of avoiding contact with potentially infected animals and reporting sick or dead wildlife to local authorities can help in early detection and intervention. Educating the public about proper waste disposal and hygiene practices can also reduce the chances of indirect transmission through contaminated environments.

Heartworm

Heartworm disease in foxes is caused by the parasitic nematode Dirofilaria immitis. This parasite primarily infects the pulmonary arteries and the heart, leading to severe cardiovascular and respiratory issues. While heartworm is well-known for affecting domestic dogs, wild canids such as foxes can also be significantly impacted. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of heartworm in foxes is essential for wildlife health management and the protection of domestic animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with heartworms may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can range from subtle to severe. Early stages of infection may be asymptomatic. As the disease progresses, common symptoms include coughing, exercise intolerance, and weight loss. Foxes may also display signs of respiratory distress, such as labored breathing and fatigue. In advanced cases, symptoms can include heart failure, marked by swelling in the abdomen due to fluid accumulation (ascites), and a pronounced lack of energy. Severe infections can lead to sudden collapse and death.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing heartworm in foxes involves a combination of clinical signs, imaging, and laboratory tests. Veterinarians often begin with a physical examination and a review of the fox's symptoms. Blood tests, particularly the antigen test, are crucial for detecting the presence of adult female heartworms. Microfilariae tests can confirm the presence of larval stages in the bloodstream. Radiographs (X-rays) and echocardiograms (ultrasound of the heart) are used to assess the extent of damage to the heart and lungs and to visualize the worms themselves. These diagnostic tools help determine the severity of the infection and guide treatment options.

Treatment

Treating heartworm in foxes is challenging and typically involves a multi-step approach. The primary treatment aims to kill the adult heartworms and larvae, using medications such as melarsomine dihydrochloride for adult worms and ivermectin for microfilariae. Supportive care is also critical, including anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce the risk of severe inflammatory reactions as the worms die. Foxes may require hospitalization for close monitoring, especially during the initial treatment phase. Managing secondary complications like heart failure involves additional medications and supportive treatments. Given the risks associated with treating heartworm, prevention is often emphasized over treatment.

Prevention

Preventing heartworm in foxes is vital to reduce the incidence and spread of this disease. Preventive measures include administering monthly heartworm prophylactics to at-risk populations, which can kill the larvae before they mature into adults. Reducing exposure to mosquitoes, which are the vectors for heartworm transmission, is another crucial strategy. This can be achieved by minimizing standing water sources and using mosquito repellents where applicable. For foxes in rehabilitation or captive settings, regular veterinary check-ups and heartworm testing can help detect and manage the disease early. Public education campaigns aimed at pet owners and wildlife rehabilitators can also play a significant role in prevention efforts, emphasizing the importance of heartworm prevention in all canid species.

Hereditary Hyperplastic Gingivitis

Hereditary Hyperplastic Gingivitis is an autosomal recessive disease that occurs mainly in male foxes, but can also occur in females, characterized by an abnormal overgrowth of the gum tissue. This condition is inherited and can significantly impact the oral health and overall well-being of affected animals. It has been noted that it is a condition related to superior coat quality, specifically; the length and density of guard hairs. The defect is present at birth. It is thought that viral infection gives rise to this phenotype expression.

"Hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis is a progressive growth of gingival tissues in foxes resulting in dental encapsulation. It is an autosomal recessive condition displaying a gender-biased penetrance, with an association with superior fur quality. This disease has been primarily described in European farmed foxes... Until 2008, HHG had only been described in the farmed fox population, at which time a case in a wild red fox was reported in Germany."

Clinical Signs

Foxes with hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis typically exhibit noticeable overgrowth of the gingival (gum) tissue. This overgrowth can cover the teeth, leading to difficulty in chewing and swallowing. Affected foxes may show signs of oral discomfort, including pawing at the mouth, drooling, and reluctance to eat hard foods. Bad breath (halitosis) and bleeding gums are also common symptoms. In severe cases, the excessive gingival tissue can lead to secondary infections and periodontal disease, further complicating the animal's condition and potentially leading to tooth loss. Clinical signs appear at around 2-3 years of age and continue throughout the fox's lifespan.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis involves a thorough oral examination by a veterinarian. The clinical signs, particularly the distinctive gingival overgrowth, are usually indicative of the condition. To confirm the diagnosis, a biopsy of the gingival tissue may be performed to rule out other causes of gingival enlargement, such as neoplasia or inflammatory conditions. Dental radiographs (X-rays) can help assess the extent of the overgrowth and its impact on the underlying teeth and bone structures. Genetic testing might also be considered to identify the hereditary nature of the condition, especially if there is a known family history of the disease.

Treatment

Treatment for hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis primarily focuses on managing the symptoms and maintaining oral health. Regular dental cleanings and professional scaling are essential to control plaque and tartar buildup, which can exacerbate the condition. In some cases, surgical removal of the excess gingival tissue (gingivectomy) may be necessary to reduce the overgrowth and improve the fox's ability to eat and maintain oral hygiene. Pain management and antibiotics might be prescribed to address discomfort and prevent secondary infections. Owners and caretakers should implement a strict oral hygiene routine, including regular brushing of the fox's teeth if possible, to help manage the condition.

Prevention

Preventing hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis involves genetic counseling and responsible breeding practices. Breeders should avoid mating foxes known to carry the genetic predisposition for this condition. Regular veterinary check-ups are crucial for early detection and management of the disease, particularly in populations with a known history of hereditary hyperplastic gingivitis. Ensuring a proper diet that promotes dental health can also help in minimizing the risk of severe gingival overgrowth. Education and awareness among wildlife rehabilitators, pet owners, and veterinarians about the hereditary nature of this condition are essential for its effective management and prevention.

The example below, by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, demonstrates how teeth may become covered by such growth.

Hookworm

Hookworm infection in foxes is caused by parasitic nematodes, primarily Ancylostoma caninum and Uncinaria stenocephala. These parasites reside in the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal lining and feed on the host's blood, leading to significant health issues. Hookworm infections are common in wild canids, including foxes, and can also affect domestic dogs and other animals. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hookworm infection is essential for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread to other animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with hookworms may exhibit a range of clinical signs, depending on the severity of the infection. Common symptoms include diarrhea, which may be bloody or tarry due to intestinal bleeding. Affected foxes often suffer from weight loss and poor body condition, despite having a normal appetite. Anemia is a significant concern in severe infections, leading to pale mucous membranes, weakness, and lethargy. In young or immunocompromised foxes, hookworm infection can be particularly devastating, causing severe dehydration, malnutrition, and even death if left untreated.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing hookworm infection in foxes involves a combination of clinical examination and laboratory tests. Veterinarians typically perform a fecal examination to identify hookworm eggs under a microscope. The presence of these characteristic eggs in the feces confirms the diagnosis. In some cases, additional tests such as a complete blood count (CBC) may be conducted to assess the severity of anemia and other related health issues. A detailed history and observation of clinical signs also aid in the diagnosis and help determine the appropriate treatment plan.

Treatment

Treating hookworm infection in foxes involves administering anthelmintic medications to kill the parasites. Commonly used drugs include fenbendazole, pyrantel pamoate, and milbemycin oxime. The specific treatment regimen depends on the severity of the infection and the overall health of the fox. Supportive care, such as fluid therapy and nutritional support, is crucial for severely affected animals, especially those with significant anemia and dehydration. Follow-up fecal examinations are necessary to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment and to detect any potential reinfection. In some cases, repeated treatments may be required to fully eradicate the parasites.

Prevention

Preventing hookworm infection in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the parasites and maintaining overall health. Regular deworming protocols for captive foxes and those in rehabilitation programs can help minimize the risk of infection. Ensuring a clean and hygienic environment, including proper disposal of feces, reduces the chances of contamination and transmission. In wild populations, managing the density and health of fox communities through wildlife management practices can help control the spread of hookworms. Public education on the risks and signs of hookworm infection is vital, particularly for those who handle or care for foxes, to promote early detection and intervention.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease in foxes is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted primarily through the bite of infected black-legged ticks (Ixodes species). This disease is widely recognized for affecting humans and domestic animals, but it also poses a significant threat to wild canids, including foxes. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease in foxes is crucial for wildlife health management and preventing the spread of this disease.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with Lyme disease may exhibit various clinical signs, though some individuals can remain asymptomatic. Common symptoms include lameness due to joint inflammation (Lyme arthritis), which may shift from one leg to another. Affected foxes may also experience fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. In more severe cases, neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination), behavioral changes, and seizures can occur. Cardiac abnormalities, although less common, may also be present. The variability of symptoms and their intermittent nature can make Lyme disease challenging to diagnose based solely on clinical signs.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Lyme disease in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians often begin with a thorough physical examination and a review of the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to tick-infested areas. Serological tests, such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot, are used to detect antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify the presence of bacterial DNA in tissue samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. Additionally, joint fluid analysis may be conducted in cases of lameness to differentiate Lyme arthritis from other causes of joint pain.

Treatment

Treatment for Lyme disease in foxes typically involves the use of antibiotics to eliminate the infection. Doxycycline is the antibiotic of choice and is usually administered for several weeks to ensure complete eradication of the bacteria. In some cases, other antibiotics such as amoxicillin may be used. Supportive care, including anti-inflammatory medications to manage pain and swelling, is also important. Rest and confinement may be necessary to minimize stress on the affected joints. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the infection is fully resolved and to prevent recurrence.

Prevention

Preventing Lyme disease in foxes involves strategies to reduce exposure to ticks and manage tick populations. Regular tick control measures, such as the use of tick repellents and acaricides, can help protect foxes in captivity or rehabilitation settings. Habitat management, including reducing dense vegetation and leaf litter where ticks thrive, can also lower the risk of tick bites. In areas where Lyme disease is prevalent, routine veterinary check-ups and prompt removal of ticks are crucial. Public education on the importance of tick prevention and early detection of Lyme disease symptoms is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. For domestic animals and humans, maintaining tick control measures can also help reduce the spillover of Lyme disease to wildlife populations.

Lungworm

Lungworm infection in foxes is primarily caused by the parasitic nematodes Angiostrongylus vasorum and Crenosoma vulpis. These parasites reside in the lungs and associated blood vessels, leading to respiratory and cardiovascular issues. While lungworm is known to affect domestic dogs, wild canids such as foxes are also susceptible. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of lungworm infection is crucial for wildlife health management and the protection of both wild and domestic animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with lungworm may exhibit a variety of clinical signs related to respiratory and cardiovascular distress. Common symptoms include coughing, which may be persistent and severe, and difficulty breathing (dyspnea). Affected foxes may also show signs of exercise intolerance, lethargy, and weight loss. In severe cases, symptoms can include wheezing, nasal discharge, and bleeding disorders due to coagulopathies caused by Angiostrongylus vasorum. Some foxes might develop secondary bacterial infections in the lungs, leading to further complications.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lungworm infection in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on respiratory symptoms. Fecal examination using the Baermann technique is commonly employed to detect lungworm larvae in the feces. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) can provide samples directly from the respiratory tract for microscopic examination. Radiographs (X-rays) of the chest can help visualize lung abnormalities and support the diagnosis. Serological tests and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing may also be used to detect specific lungworm species.

Treatment

Treating lungworm infection in foxes involves administering anthelmintic medications to eliminate the parasites. Commonly used drugs include fenbendazole, ivermectin, and milbemycin oxime. The specific treatment regimen depends on the severity of the infection and the overall health of the fox. Supportive care is crucial, especially for severely affected animals, and may include oxygen therapy, antibiotics for secondary infections, and anti-inflammatory medications to reduce lung inflammation. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up fecal examinations are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent reinfection.

Prevention

Preventing lungworm infection in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the parasites and maintaining overall health. Regular deworming protocols for captive foxes and those in rehabilitation programs can help minimize the risk of infection. Ensuring a clean and hygienic environment, including proper disposal of feces, reduces the chances of contamination and transmission. Wildlife management practices, such as controlling intermediate hosts (snails and slugs) in the environment, can also help limit the spread of lungworm. Public education on the risks and signs of lungworm infection is vital, particularly for those who handle or care for foxes, to promote early detection and intervention. For domestic dogs and cats, maintaining regular deworming and tick control measures can also help reduce the spillover of lungworm to wildlife populations.

Ringworm

Ringworm in foxes is a dermatophyte infection caused by various fungal species, primarily Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Despite its name, ringworm is not caused by a worm but by fungi that infect the skin, hair, and nails. This zoonotic infection can affect a wide range of animals, including wild canids like foxes, as well as humans. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of ringworm is essential for managing the health of fox populations and preventing its spread to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with ringworm typically exhibit a range of dermatological symptoms. Common signs include circular, crusty, and scaly patches of hair loss (alopecia) on the skin, often with a red, inflamed border. These lesions can appear on various parts of the body but are frequently found on the face, ears, and limbs. Affected foxes may experience itching and scratching, leading to secondary bacterial infections. In some cases, the claws and nail beds can also be affected, resulting in brittle or deformed claws. The severity of symptoms can vary, with some foxes showing only mild signs while others develop extensive lesions.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ringworm in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination, focusing on the characteristic skin lesions. Wood's lamp examination can be used to identify certain species of dermatophytes that fluoresce under ultraviolet light, although this method is not definitive. More conclusive diagnostic methods include microscopic examination of hair and skin scrapings to detect fungal spores and cultures of these samples to identify the specific fungal species. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing may also be employed for rapid and accurate identification of the dermatophytes.

Treatment

Treating ringworm in foxes involves both topical and systemic antifungal therapies. Topical treatments include antifungal creams, ointments, or medicated shampoos containing active ingredients like miconazole, clotrimazole, or terbinafine, which are applied directly to the affected areas. Systemic treatments, such as oral antifungal medications like itraconazole or terbinafine, are often necessary for more severe or widespread infections. It is crucial to continue treatment for several weeks, even after clinical signs have resolved, to ensure complete eradication of the infection. In addition to medical treatment, thorough cleaning and disinfection of the fox's environment are essential to prevent reinfection and spread to other animals.

Prevention

Preventing ringworm in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the fungi and maintaining overall health. Regular veterinary check-ups and prompt treatment of any skin lesions can help minimize the risk of ringworm. In captive or rehabilitated fox populations, maintaining a clean and hygienic environment is crucial, including regular cleaning and disinfection of enclosures and bedding. Reducing stress and ensuring proper nutrition can also support the fox's immune system, making them less susceptible to infections. Public education on the risks and signs of ringworm is vital, particularly for those who handle or care for foxes, to promote early detection and intervention. For domestic animals and humans, good hygiene practices and prompt treatment of any suspected ringworm infections can help reduce the spillover of this zoonotic disease to wildlife populations.

Roundworm

Roundworm infection in foxes is primarily caused by the parasitic nematode Toxocara canis. These worms inhabit the intestines of the host, where they can cause significant health issues. Roundworm infections are common in both wild and domestic canids, posing a risk to wildlife health and potentially spreading to other animals and humans. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of roundworm infection is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing zoonotic transmission.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with roundworms may exhibit a range of clinical signs, particularly in severe infections. Common symptoms include a pot-bellied appearance, poor coat condition, and weight loss despite a normal or increased appetite. Affected foxes may also experience gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. In young foxes, heavy infestations can lead to stunted growth and developmental issues. In severe cases, roundworms can cause intestinal blockages or migrate to other organs, leading to respiratory symptoms like coughing and difficulty breathing due to larval migration through the lungs.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing roundworm infection in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Fecal examination using flotation techniques is the primary method for diagnosing roundworms, as it allows the identification of characteristic eggs in the feces. In some cases, adult worms may be visible in vomit or feces. Additional tests, such as bloodwork, may be conducted to assess the overall health of the fox and identify any complications arising from the infection.

Treatment

Treating roundworm infection in foxes involves administering anthelmintic medications to eliminate the parasites. Commonly used drugs include pyrantel pamoate, fenbendazole, and ivermectin. The specific treatment regimen depends on the severity of the infection and the overall health of the fox. In some cases, repeated treatments may be necessary to address re-infections or ensure complete eradication of the parasites. Supportive care, such as maintaining hydration and addressing any secondary infections or complications, is also important. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up fecal examinations are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent reinfection.

Prevention

Preventing roundworm infection in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the parasites and maintaining overall health. Regular deworming protocols for captive foxes and those in rehabilitation programs can help minimize the risk of infection. Ensuring a clean and hygienic environment, including proper disposal of feces, reduces the chances of contamination and transmission. Wildlife management practices, such as controlling intermediate hosts (small mammals) in the environment, can also help limit the spread of roundworms. Public education on the risks and signs of roundworm infection is vital, particularly for those who handle or care for foxes, to promote early detection and intervention. For domestic animals and humans, maintaining regular deworming and hygiene practices can also help reduce the spillover of roundworms to wildlife populations.

Rickettsia

Rickettsia infection in foxes is caused by various species of Rickettsia bacteria, which are obligate intracellular pathogens. These bacteria are transmitted primarily through the bites of infected ticks, fleas, and lice. Rickettsial diseases are known to affect a wide range of animals, including wild canids like foxes, and can also be transmitted to humans, posing a significant zoonotic risk. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rickettsia infection is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of these bacteria to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with Rickettsia may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the specific Rickettsia species involved. Common symptoms include fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also show signs of respiratory distress, such as coughing and difficulty breathing, and gastrointestinal issues like vomiting and diarrhea. In some cases, neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination), seizures, and behavioral changes can occur. Foxes with Rickettsia infection may also develop skin lesions, including rashes and ulcers at the site of tick bites.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Rickettsia infection in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to ticks and other ectoparasites. Blood tests, including serology (such as indirect immunofluorescence assay or ELISA), are used to detect antibodies against Rickettsia species. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify Rickettsia DNA in blood or tissue samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. In some cases, biopsy and histopathological examination of skin lesions or other affected tissues may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treating Rickettsia infection in foxes involves the use of antibiotics to eliminate the bacteria. Doxycycline is the antibiotic of choice and is typically administered for several weeks to ensure complete eradication of the infection. In some cases, other antibiotics such as tetracycline or chloramphenicol may be used. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and anti-inflammatory medications, is crucial for managing symptoms and ensuring the fox's recovery. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent relapse.

Prevention

Preventing Rickettsia infection in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to ticks and other ectoparasites and maintaining overall health. Regular use of tick prevention measures, such as topical acaricides or tick collars, can help protect foxes in captivity or rehabilitation settings. Habitat management, including reducing dense vegetation and controlling rodent populations, can lower the risk of tick bites. Public education on the importance of tick prevention and early detection of Rickettsia symptoms is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. For domestic animals and humans, maintaining tick control measures and practicing good hygiene can help reduce the spillover of Rickettsia to wildlife populations. Additionally, monitoring and controlling ectoparasite infestations in wild fox populations can help limit the spread of these bacteria.

Sarcoptic Mange

Mange in foxes is a highly contagious skin disease caused by mites, primarily Sarcoptes scabiei, which leads to sarcoptic mange. This condition causes severe itching, hair loss, and skin lesions. Mange is prevalent in wild canid populations, including foxes, and can spread rapidly, significantly impacting the health and survival of affected individuals. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mange is crucial for wildlife health management and reducing its spread to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with mange mites exhibit a range of clinical signs that can be severe and debilitating. Early symptoms include intense itching and scratching, leading to the formation of red, inflamed skin. As the disease progresses, affected foxes develop hair loss (alopecia), crusty scabs, and thickened, wrinkled skin, especially around the face, ears, legs, and tail. Secondary bacterial infections are common due to open wounds and constant scratching. In severe cases, mange can lead to weight loss, dehydration, and lethargy, significantly reducing the fox's ability to hunt and care for itself. Without treatment, severe mange infections can be fatal.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing mange in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination, focusing on the characteristic skin lesions and signs of itching. Skin scrapings from the affected areas are examined under a microscope to identify the presence of Sarcoptes scabiei mites or their eggs. In some cases, a biopsy of the skin may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other skin conditions. Serological tests can also be used to detect antibodies against mange mites, providing further evidence of infection.

Treatment

Treating mange in foxes involves eliminating the mites and managing the associated skin lesions and secondary infections. Commonly used medications include topical acaricides such as selamectin or moxidectin, and systemic treatments like ivermectin or milbemycin. These medications are often administered multiple times over several weeks to ensure complete eradication of the mites. Supportive care, including antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections and anti-inflammatory medications to reduce itching and inflammation, is also important. In captive or rehabilitated foxes, maintaining a clean environment and providing proper nutrition can support the healing process. Regular follow-up examinations are necessary to monitor the fox's response to treatment and prevent reinfection.

Prevention

Preventing mange in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the mites and maintaining overall health. Regular use of acaricides in captive or rehabilitated fox populations can help minimize the risk of infestation. Ensuring a clean and hygienic environment, including regular cleaning and disinfection of enclosures and bedding, reduces the chances of mite transmission. Wildlife management practices, such as controlling population density and monitoring health, can help limit the spread of mange in wild fox populations. Public education on the signs of mange and the importance of early detection and treatment is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. For domestic animals and humans, practicing good hygiene and implementing regular parasite control measures can help reduce the spillover of mange to wildlife populations. Additionally, quarantining and treating newly introduced animals can prevent the introduction of mange into healthy populations.

Tapeworm

Introduction and Background

Tapeworm infection in foxes is primarily caused by the Echinococcus multilocularis and Taenia spp. Tapeworms are parasitic flatworms that inhabit the intestines of their hosts. Foxes, both wild and domestic, are definitive hosts for these tapeworms, meaning the parasites reach sexual maturity within them. These infections are of significant concern not only for the health of fox populations but also because they pose a zoonotic risk to humans and domestic animals. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of tapeworm infections in foxes is crucial for managing these parasites and reducing the risk of transmission.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with tapeworms often exhibit minimal to no overt clinical signs, making the detection of these parasites challenging. However, in cases of heavy infestations, foxes may show symptoms such as weight loss, poor coat condition, and diarrhea. The presence of tapeworm segments around the anal area or in feces is a common indicator of infection. Severe cases may lead to abdominal discomfort and, in rare instances, intestinal blockage.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing tapeworm infection in foxes involves a combination of fecal examination and serological tests. A veterinarian will typically perform a fecal flotation test to identify the presence of tapeworm eggs or segments in the fox's feces. In some instances, PCR testing can be used to detect tapeworm DNA in fecal samples, providing a more precise identification of the parasite species. Additionally, coproantigen ELISA tests can be employed to detect specific tapeworm antigens in feces, further confirming the infection.

Treatment

Treatment of tapeworm infection in foxes primarily involves the use of anthelmintic medications. Praziquantel is the drug of choice, known for its efficacy in eliminating tapeworms. This medication is typically administered as a single dose but may need to be repeated depending on the severity of the infection and the risk of re-infection. In addition to anthelmintic treatment, supportive care, such as nutritional support and management of secondary symptoms, is important to ensure the fox's recovery.

Prevention

Preventing tapeworm infection in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to intermediate hosts and maintaining overall health. Key prevention measures include:

- Control of Intermediate Hosts: Since rodents are common intermediate hosts for tapeworms, controlling rodent populations around fox habitats can significantly reduce the risk of infection.

- Regular Deworming: Routine administration of anthelmintic medications to foxes, particularly in captive or rehabilitation settings, helps to prevent and control tapeworm infections.

- Public Education: Educating the public, especially those who work with or rehabilitate foxes, about the importance of tapeworm prevention and the risks of zoonotic transmission is crucial.

- Environmental Management: Keeping the fox’s environment clean and minimizing their exposure to potential sources of tapeworm eggs, such as infected prey, can help reduce infection rates.

By implementing these preventive measures and ensuring regular health checks, the spread of tapeworm infections in fox populations can be effectively managed, safeguarding both animal and human health.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis in foxes is caused by the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. This parasite has a complex life cycle involving various hosts, including wild canids like foxes, which can act as intermediate hosts. T. gondii is transmitted through ingestion of contaminated food or water, or by consuming infected prey. Toxoplasmosis is a significant zoonotic concern, as the parasite can infect humans and domestic animals, leading to severe health issues. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of toxoplasmosis in foxes is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of this parasite to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with T. gondii may exhibit a range of clinical signs, although many infected animals remain asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur, they can include lethargy, loss of appetite, and weight loss. Neurological signs such as ataxia (loss of coordination), seizures, and behavioral changes can also be observed. Respiratory distress, such as coughing and difficulty breathing, and gastrointestinal symptoms like vomiting and diarrhea may occur in some cases. In pregnant foxes, toxoplasmosis can lead to reproductive issues, including abortion or stillbirth.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing toxoplasmosis in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history. Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test, are used to detect antibodies against T. gondii. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify T. gondii DNA in blood, tissue, or fecal samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. In some cases, biopsy and histopathological examination of affected tissues, such as the brain or lungs, may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treating toxoplasmosis in foxes involves the use of antiprotozoal medications to reduce the parasite load. The drug of choice is typically a combination of sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine, administered for several weeks to ensure the effective management of the infection. Clindamycin is another commonly used antibiotic for treating toxoplasmosis. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and nutritional support, is crucial for managing symptoms and aiding recovery. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent relapse.

Prevention

Preventing toxoplasmosis in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to T. gondii and maintaining overall health. Key prevention measures include reducing the population of small mammals and birds, which can act as intermediate hosts for T. gondii, in and around fox habitats to lower the risk of infection. Ensuring clean and uncontaminated food and water sources for foxes, particularly in captive or rehabilitation settings, can help prevent ingestion of the parasite. Implementing effective rodent control measures can minimize the risk of foxes contracting toxoplasmosis through the consumption of infected prey. Educating the public, especially those who handle or care for foxes, about the importance of preventing T. gondii infection and the risks of zoonotic transmission is crucial. Additionally, routine health checks and monitoring for signs of toxoplasmosis in fox populations can help detect and manage infections early, reducing the overall spread of the parasite.

Anaplasmosis

Anaplasmosis in foxes is caused by various species of Anaplasma bacteria, which are obligate intracellular pathogens. These bacteria are transmitted primarily through the bites of infected ticks. Anaplasmosis is known to affect a wide range of animals, including wild canids like foxes, and can also be transmitted to humans, posing a significant zoonotic risk. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of anaplasmosis is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of these bacteria to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with Anaplasma may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the specific Anaplasma species involved. Common symptoms include fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also show signs of joint pain and lameness, which are characteristic of the disease. In some cases, neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination) and seizures can occur. Hematological signs, including anemia and thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), may also be present. Additionally, foxes with anaplasmosis may develop swollen lymph nodes and display signs of general weakness.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing anaplasmosis in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to ticks. Blood tests, including serology (such as indirect immunofluorescence assay or ELISA), are used to detect antibodies against Anaplasma species. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify Anaplasma DNA in blood or tissue samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. Blood smears may also be examined under a microscope to detect the presence of Anaplasma organisms within red blood cells.

Treatment

Treating anaplasmosis in foxes involves the use of antibiotics to eliminate the bacteria. Doxycycline is the antibiotic of choice and is typically administered for several weeks to ensure complete eradication of the infection. In some cases, other antibiotics such as tetracycline may be used. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and anti-inflammatory medications, is crucial for managing symptoms and ensuring the fox's recovery. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent relapse.

Prevention

Preventing anaplasmosis in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to ticks and maintaining overall health. Regular use of tick prevention measures, such as topical acaricides or tick collars, can help protect foxes in captivity or rehabilitation settings. Habitat management, including reducing dense vegetation and controlling rodent populations, can lower the risk of tick bites. Public education on the importance of tick prevention and early detection of anaplasmosis symptoms is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. For domestic animals and humans, maintaining tick control measures and practicing good hygiene can help reduce the spillover of Anaplasma to wildlife populations. Additionally, monitoring and controlling ectoparasite infestations in wild fox populations can help limit the spread of these bacteria.

Babesiosis

Babesiosis in foxes is caused by various species of Babesia protozoa, which are obligate intracellular parasites. These protozoa are transmitted primarily through the bites of infected ticks. Babesiosis is known to affect a wide range of animals, including wild canids like foxes, and can also be transmitted to humans, posing a significant zoonotic risk. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of babesiosis is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of these parasites to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with Babesia may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the specific Babesia species involved. Common symptoms include fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also show signs of anemia, such as pale mucous membranes and weakness, due to the destruction of red blood cells by the parasite. Jaundice, characterized by yellowing of the skin and eyes, and dark-colored urine may also be present. In severe cases, respiratory distress, such as rapid breathing and coughing, can occur. Neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination) and seizures may be observed in advanced stages of the disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing babesiosis in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to ticks. Blood smears examined under a microscope can reveal the presence of Babesia organisms within red blood cells. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify Babesia DNA in blood samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. Serological tests, such as indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), can detect antibodies against Babesia species, supporting the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treating babesiosis in foxes involves the use of antiprotozoal medications to eliminate the parasites. The combination of atovaquone and azithromycin is commonly used and has been shown to be effective. In some cases, imidocarb dipropionate may be administered. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and blood transfusions, is crucial for managing symptoms and aiding recovery, particularly in cases of severe anemia. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent relapse.

Prevention

Preventing babesiosis in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to ticks and maintaining overall health. Regular use of tick prevention measures, such as topical acaricides or tick collars, can help protect foxes in captivity or rehabilitation settings. Habitat management, including reducing dense vegetation and controlling rodent populations, can lower the risk of tick bites. Public education on the importance of tick prevention and early detection of babesiosis symptoms is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. For domestic animals and humans, maintaining tick control measures and practicing good hygiene can help reduce the spillover of Babesia to wildlife populations. Additionally, monitoring and controlling ectoparasite infestations in wild fox populations can help limit the spread of these parasites.

Canine Distemper

Canine distemper in foxes is caused by the canine distemper virus (CDV), a highly contagious paramyxovirus. The virus is transmitted primarily through direct contact with infected animals or their bodily fluids, as well as through aerosol droplets. Canine distemper is known to affect a wide range of carnivores, including wild canids like foxes, and poses a significant threat to wildlife populations. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of canine distemper is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of the virus to other animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with canine distemper may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the severity of the infection and the stage of the disease. Early symptoms often include fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also show signs of respiratory distress, such as coughing, nasal discharge, and difficulty breathing. Gastrointestinal issues, including vomiting and diarrhea, are also common. As the disease progresses, neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination), seizures, and behavioral changes can occur. Foxes with canine distemper may also develop thickened footpads and nasal planum, a condition known as hyperkeratosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing canine distemper in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to other canids or wildlife. Blood tests, including serology (such as indirect immunofluorescence assay or ELISA), are used to detect antibodies against CDV. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify CDV RNA in blood, tissue, or swab samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. In some cases, histopathological examination of tissues from deceased animals can confirm the presence of characteristic lesions associated with canine distemper.

Treatment

Treating canine distemper in foxes involves supportive care to manage symptoms and secondary infections, as there is no specific antiviral treatment for CDV. Antibiotics may be prescribed to treat secondary bacterial infections, and anti-inflammatory medications can help reduce inflammation and fever. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and nutritional support, is crucial for aiding recovery. Anticonvulsant medications may be used to control seizures in foxes with neurological symptoms. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and providing ongoing care are essential to improve the chances of recovery.

Prevention

Preventing canine distemper in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the virus and maintaining overall health. Vaccination is the most effective measure for preventing CDV infection in captive or rehabilitated foxes. Regular vaccination schedules should be maintained to ensure continued immunity. Reducing contact between foxes and domestic dogs, which can be carriers of CDV, is important for minimizing the risk of transmission. Public education on the importance of vaccination and the risks of CDV is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. Additionally, monitoring and controlling outbreaks in wild fox populations through vaccination campaigns and surveillance can help limit the spread of the virus.

Canine Parvovirus

Canine parvovirus (CPV) in foxes is caused by a highly contagious virus that affects the gastrointestinal tract and, in severe cases, the heart. The virus is transmitted primarily through direct contact with infected animals or their feces, and it can also survive in the environment for long periods. Canine parvovirus affects a wide range of canids, including wild foxes, posing a significant threat to wildlife populations. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of canine parvovirus is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of the virus to other animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with canine parvovirus may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the severity of the infection. Common symptoms include severe vomiting, diarrhea (often bloody), and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also show signs of dehydration, lethargy, and weight loss due to the rapid loss of fluids and nutrients. In severe cases, foxes can develop sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by the spread of bacteria from the damaged intestines into the bloodstream. Young foxes, in particular, may suffer from myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), leading to sudden death.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing canine parvovirus in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on exposure to other canids or contaminated environments. Fecal tests, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), are used to detect CPV antigens or DNA in the stool, providing definitive evidence of infection. Blood tests may also be conducted to assess the fox's overall health and identify signs of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and secondary infections.

Treatment

Treating canine parvovirus in foxes involves aggressive supportive care to manage symptoms and prevent secondary infections, as there is no specific antiviral treatment for CPV. Treatment typically includes intravenous fluids to combat dehydration, electrolyte supplementation, and anti-nausea medications to control vomiting. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent or treat secondary bacterial infections. Nutritional support, either through feeding tubes or specialized diets, is crucial for maintaining the fox's strength and aiding recovery. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and providing ongoing care are essential to improve the chances of recovery.

Prevention

Preventing canine parvovirus in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the virus and maintaining overall health. Vaccination is the most effective measure for preventing CPV infection in captive or rehabilitated foxes. Regular vaccination schedules should be maintained to ensure continued immunity. Good hygiene practices, such as regular cleaning and disinfection of enclosures and equipment, can help reduce the risk of environmental contamination. Public education on the importance of vaccination and the risks of CPV is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. Additionally, reducing contact between foxes and domestic dogs, which can be carriers of CPV, is important for minimizing the risk of transmission. Monitoring and controlling outbreaks in wild fox populations through vaccination campaigns and surveillance can help limit the spread of the virus.

Cat Scratch Disease

Cat scratch disease (CSD) in foxes is caused by the bacterium Bartonella henselae. This bacterium is primarily transmitted through the scratch or bite of infected cats, which are the main reservoir hosts. Although CSD is more commonly associated with domestic cats and humans, it can affect a wide range of animals, including wild canids like foxes. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cat scratch disease is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of the bacterium to other animals and humans.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with Bartonella henselae may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, although many infected animals may be asymptomatic. Common symptoms include fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Affected foxes may also develop swollen lymph nodes, particularly near the site of the scratch or bite. In some cases, foxes may show signs of more severe systemic illness, including weight loss, muscle pain, and neurological symptoms such as ataxia (loss of coordination) and seizures. Skin lesions, such as pustules or abscesses, may develop at the site of the initial wound.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing cat scratch disease in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on potential exposure to cats. Blood tests, including serology (such as indirect immunofluorescence assay or ELISA), are used to detect antibodies against Bartonella henselae. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify Bartonella DNA in blood or tissue samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. In some cases, biopsy and histopathological examination of affected lymph nodes or skin lesions may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treating cat scratch disease in foxes involves the use of antibiotics to eliminate the bacterium. Azithromycin is commonly used and has been shown to be effective. In some cases, other antibiotics such as doxycycline or rifampin may be used. Supportive care, including fluid therapy and anti-inflammatory medications, is crucial for managing symptoms and ensuring the fox's recovery. Monitoring the fox's response to treatment and conducting follow-up tests are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the therapy and prevent relapse.

Prevention

Preventing cat scratch disease in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to Bartonella henselae and maintaining overall health. Key prevention measures include reducing interactions between foxes and domestic cats, which are the primary carriers of the bacterium. Ensuring that any scratches or bites received by foxes are promptly cleaned and treated can help prevent infection. Public education on the risks of CSD and the importance of minimizing contact between wildlife and domestic animals is crucial for those who handle or care for foxes. Additionally, monitoring and controlling flea infestations in both wild and captive fox populations can help reduce the risk of transmission, as fleas can play a role in spreading Bartonella bacteria.

Canine Herpesvirus

Canine herpesvirus (CHV) in foxes is caused by the canine herpesvirus-1 (CHV-1), a highly contagious virus belonging to the Herpesviridae family. This virus primarily affects young puppies, but can also infect adult canids, including wild foxes. CHV is transmitted through direct contact with infected animals or their bodily fluids, as well as through aerosol droplets. Understanding the clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of canine herpesvirus is crucial for managing the health of fox populations and preventing the spread of the virus to other animals.

Clinical Signs

Foxes infected with canine herpesvirus may exhibit a variety of clinical signs, which can vary depending on the age and immune status of the animal. In young fox pups, CHV can cause severe, often fatal, generalized infections. Symptoms include weakness, crying, loss of appetite, and difficulty breathing. Hemorrhages may be visible on the mucous membranes, and abdominal pain is common. Older foxes and adults often show milder signs, which can include respiratory symptoms such as coughing, nasal discharge, and conjunctivitis. Reproductive issues, including infertility, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths, can also occur in breeding foxes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing canine herpesvirus in foxes involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Veterinarians typically start with a thorough physical examination and review the fox's medical history, focusing on potential exposure to other canids. Blood tests, including serology (such as indirect immunofluorescence assay or ELISA), are used to detect antibodies against CHV-1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify CHV-1 DNA in blood, tissue, or swab samples, providing definitive evidence of infection. In cases of neonatal death, histopathological examination of tissues can reveal characteristic lesions associated with CHV-1 infection.

Treatment

Treating canine herpesvirus in foxes focuses on supportive care, as there is no specific antiviral treatment for CHV-1. For young fox pups, intensive supportive care, including maintaining body temperature, providing fluids, and ensuring adequate nutrition, is crucial. Antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent or treat secondary bacterial infections. For older foxes, symptomatic treatment for respiratory or ocular symptoms may be required. In breeding foxes, managing reproductive issues and monitoring pregnant females closely can help mitigate the impact of the virus.

Prevention

Preventing canine herpesvirus in foxes involves several strategies aimed at reducing exposure to the virus and maintaining overall health. Isolating pregnant females and young pups from other canids, particularly during the last three weeks of pregnancy and the first three weeks of the pups' lives, can help prevent transmission. Good hygiene practices, such as regular cleaning and disinfection of enclosures and equipment, can reduce the risk of environmental contamination. Public education on the importance of preventing CHV-1 and the risks associated with the virus is vital for those who handle or care for foxes. Monitoring and controlling outbreaks in wild fox populations through surveillance can help limit the spread of the virus. Additionally, ensuring that foxes in captive breeding programs are free from CHV-1 can help protect future generations.

Chaztek Paralysis

Chaztek Paralysis is a disease first recognized in the Silver fox. It refers to the presence of neurological symptoms, as a result of lesions in the central nervous system, which are secondary manifestation of a thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency from feeding too much of certain types of uncooked whole fish. Cases are typically limited to fur farms that feed whole fish diets, but in 2007, Chaztek paralysis was recorded in 2 wild foxes (vulpes vulpes japonica).

"Chastek paralysis, an acute dietary disease of foxes, is caused by including 10% or more of certain species of uncooked fish in the diet and may be prevented or cured by giving adequate amounts of thiamine"

Physiological Availability of the Vitamins - Daniel Melnick, 1945

Clinical Signs