Polymorphism In Red Foxes

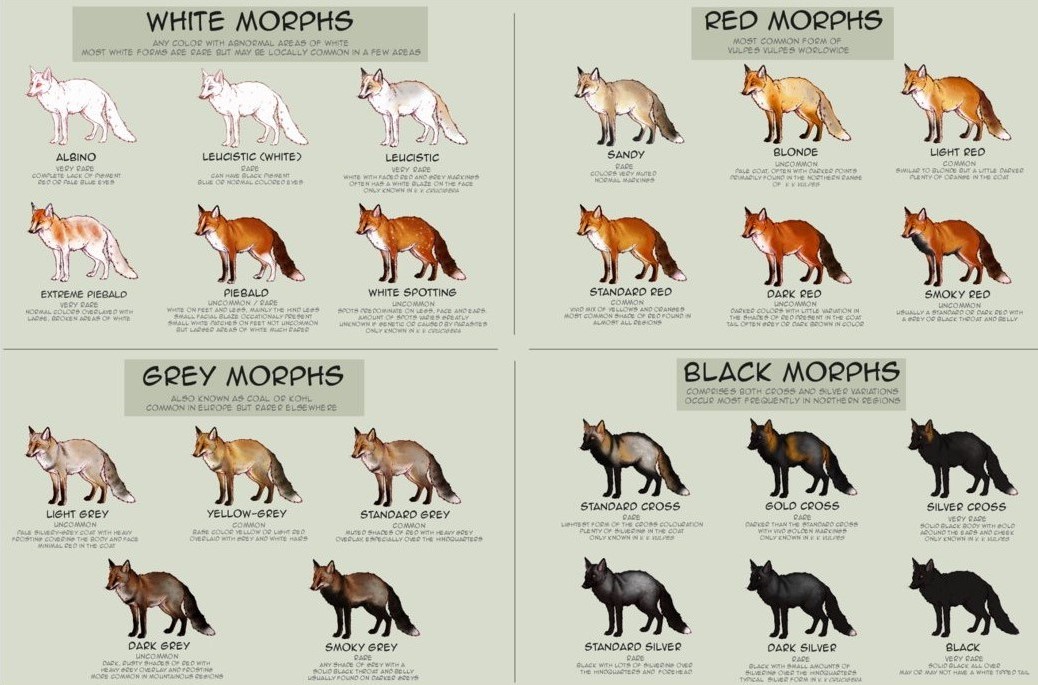

The vast majority of foxes in the UK are red in colour, but black (melanistic) and white (leucistic and albino) foxes are occasionally spotted from time to time. Foxes with white patches (piebald foxes) are relatively common in comparison, especially in urban areas. The frequency of black foxes seen in the UK has been historically low and such sightings appear far less frequently than in other areas of the world (less than 0.1% of the population, by our records). For this reason, black foxes have been a thing of myth and folklore within the UK—more on UK red fox polymorphism, here.

This is a stark contrast to what is seen in Canada and North America, where the North American red fox displays a greater degree of coat variation and is included as part of the rich cultural heritage of the native peoples and early settlers. The North American red fox occurs in three common colours or 'phenotypes' which are naturally present in statistically predictable frequencies; red (approx. 51-75%), cross (approx. 22-41%) and silver (approx. 2-8%).

"The [silver fox] is very rare... It inhabits the same districts with the red fox. It is not yet clearly proved that it is of the same species as the black fox of Europe [which natural historians describe as being of a pure shining black] though it bares a strong resemblance to it… The common fox of America is supposed by Cuvier to be a distinct species from the red fox of Europe. It inhabits all parts of the United States."

The Silver Fox: The American Fox (1853) / The Family Magazine, Or, General Abstract of Useful Knowledge, Volume 2 (1843)

Naturally Occurring Red Fox Colour Mutations (based on the North American red fox):

©2014-2015 Urban Mongoose - Red Fox Colour Mutations

©2017 Black Foxes UK Reporter - Melanistic European Red fox

Despite wild melanistic red foxes being present in the UK, the majority of black and usually coloured foxes reported to ourselves and in the media are escaped exotic pets, which are collectively called 'silver foxes' after the line from which they originate. The majority of these escapees are re-captured within a week. Being nervous timid animals, they pose little threat while they are out and will only bite in defense (just as with our wild foxes). Sadly, without any skills to find food or navigate busy roads, they are at a high risk of being involved in a road traffic accident (especially at night) and not all lost silver foxes are lucky enough to make it home (which is why reporting sightings and locating lost silver foxes is so important).

The silver fox has been selectively bred for the fur trade for over 150 years, displaying genetic, physical and behavioural differences in comparison to it's wild counterpart as a result. The selective breeding of silver foxes for the fur trade created a domesticated farm animal that now comes in a range of over 70 different colour morphs, possessing genetic mutations that could not exist naturally in wild populations. In addition to this, scientists then spent over 60 years selectively breeding these silver foxes for desired behaviour, resulting in a line of foxes that can be classified as domesticated pets, having been scientifically domesticated for tame behaviour towards humans.

The terms 'domesticated' and 'tame' are not synonymous. Domestication is the process of human-selected evolutionary development, tameness is a trait we select for in that process. The terms 'pet' and 'tame' are synonymous. Thus, a 'domesticated farm animal' (domesticated for physical traits) is not the same thing as a 'domesticated pet' (domesticated for tame behaviour).

A wild animal can be tamed or made a 'pet' given nurture, but it is not a 'domesticated pet' (domesticated specifically for tame behaviour - Where the nature of the animal has been changed on a genetic level, in that it is then passed down to subsequent generations). A wild animal is said to be 'self-domesticating' when their evolutionary development is considered human-driven, but not through captive-bred selection.

© 2015 J. Morrell - Feral North American Red Fox Hybrid

Fur farming ended in the UK at the turn of the millennium. However, escapes and releases did occur when the industry was still here and thriving. Despite the UK ban and the global movement to ban fur farming, London remains a world center for fur buyers, with the International Fur Federation being based in our capital city. It is an industry that produces 15 million fox pelts a year, with up to 70% of the fur industry's production of fox fur originating from Europe alone.

Hybrids between the North American red fox and the European red fox are possible, as they are both vulpes vulpes. Though it is interesting to note that the North American red fox and the European red fox were once classified as two separate species; vulpes vulpes in Eurasia and vulpes fulva in the America's (Tesky, 1995), being considered a singular species since 1959 (based on anecdotal reports). Modern technology however, has recently provided evidence that our original assumption on species divergence may have been correct, detecting two distinct red fox lineages that were isolated from each other during the last glaciation.

© 2010 Mike Warburton Photography - Feral North American Red Fox Hybrid

© 2016 Carissa Twloha Marie - Arctic Fox Red Fox Hybrid

Hybrids between the Red fox and the Arctic fox have also been recorded within both wild and captive bred populations in the US, but those reported in the wild are thought to be escaped farm stock; given the complex artificial insemination techniques required to produce such a hybrid on fur farms. There have been no sightings on UK shores of any such hybrids but it is important to note that both Silver foxes and 'Blue foxes' (the domesticated Arctic fox) were once bred here by the fur trade and both species are kept here as exotic pets today. There have been a handful of 'white fox' sightings reported in the UK, which are noted to have been that of lost, captive-bred Arctic foxes.

The increase of unusually coloured foxes seen in the UK fox population coincides with the keeping of foxes as exotic pets and animal ambassadors. While anomalous coat colours do occur naturally, some do not and are a product of domestication processes. Previous sightings have occurred far less frequently than they have over recent years and due to the physical appearance of some of the individuals identified in reports, it is clear that some of the sightings have not been that of native foxes.

For more information on the red fox, please visit The Fox Website and Wildlife Online. For more on silver fox colour mutations, please visit our Silver Fox Colour guide.

Melanism & Fox Genetics

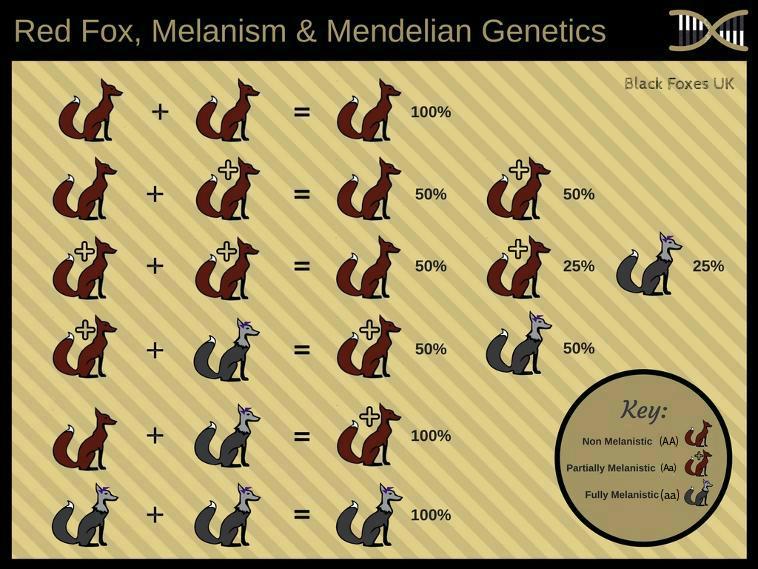

Melanism is a recessive trait that allows for greater expression of the pigment melanin in an animals skin or coat, which gives the animal a darker colouration. Melanistic coat colouration's are a rare genetic trait in UK red foxes, as both parents must carry the recessive gene for full melanism to be expressed. In the wild, melanistic foxes would rarely get the opportunity to reproduce with other foxes of the same colour morph but in farms, silver foxes are explicitly bred with others that share the same recessive melanistic trait. This selective breeding has resulted in colour mutations that do not exist in wild populations (this includes luecistic, white and red forms e.g. 'cherry red fox') and has altered the physiological and behavioural profile of the silver fox in comparison to it's wild cousin.

"Psysiological causes of coloration, including melanism, are evident but poorly researched. The relative importance of evolutionary forces responsible for external coloration varies greatly between vertebrate taxa, but the reasons for this variation are not yet understood"

The Adaptive Significance Of Coloration In Mammals, BioScience 2015

"Overall, silver foxes account for about 10% of colour morphs. Jet black foxes are, however, very rare in Europe; in his 2005 Carnivores of the World, Ronald Nowak notes that such foxes are confined to the extreme north of Europe and make up about 1% of the population"

Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes): Wildlife Online (Updated 3rd July 2015)

Inheritance of melanism in red foxes can be explained through Mendelian genetics, first proposed by Gregor Mendel is 1865;

"Prior to Mendel, most people believed inheritance was due to a blending of parental ‘essences’, much like how mixing blue and yellow paint will produce a green color. Mendel instead believed that heredity is the result of discrete units of inheritance, and every single unit (or gene) was independent in its actions in an individual’s genome."

Mendelian Genetics - Genetics Generation

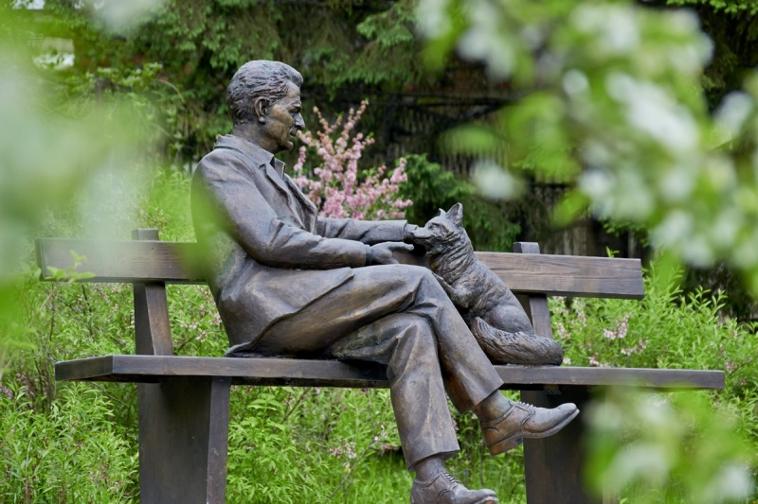

Belyaev's farm fox experiment demonstrated how Mendel's theories were correct, disproving Lamarack's theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics and the Lysenkoism opposition which dominated at the time. Today, we consider Mendel's theories the cornerstone of modern day genetics, with Belyaev's farm fox experiment sparking the emergence of new fields of scientific research into genetics, domestication, epigenetics (how environment influences genes) and human and animal medicine.

"Belyaev knew his genetics and firmly believed that Lysenko's views were false.. working as a young man at the Central Research Laboratory of Fur Breeding in Moscow, he rashly expressed his opposition. He was fired from his job as a result... Belyaev searched for a topic that was scientifically interesting but not politically dangerous. He felt drawn to the issue of animal domestication. He chose [fur] foxes, common in Siberia... [a result of Russian explorers and the fur trade]"

Lysenko's Ghost: The Friendly Siberian Foxes - Loren Graham

"Belyayev's experiments were the result of a politically motivated demotion in response to defying the now discredited non-Mendellian theories of Lysenkoism, which wee politically accepted in the Soviet Union at the time.

Dmitry Belyayev (zoologist) - Ranker

In August 2017, to show their respect to the scientific contribution of Dmitry Belyaev, the Institute of Cytology and Genetics held a conference and erected a monument in his honour, commemorating the 100th anniversary of his birth.

© 1996-2019 Institute of Cytology and Genetics - Domesticated Fox Monument

Red Fox, Melanism & Mendelian Genetics: Why Are Black Foxes So Rare?

UK Fox Genetics:

While there is much research on foxes, there is very little research into the population genetics of both captive-bred and wild red foxes in the UK. Research is now beginning to focus on this field of study and tests are being developed to help distinguish different genetic populations.

"There are no published reports on the population genetics of foxes in Britain. In this study, we aim to provide an insight into recent historical movement of foxes within Britain, as well as a current assessment of the genetic diversity and gene flow within British populations"

Population Genetic Structure Of The Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes ) In The UK: Helen Atterby et al. (December 2014)

Initial results from the latest research demonstrates it is possible to distinguish wild foxes from captive bred foxes, as well as distinguishing between regional differences in the genetics of wild and farmed foxes. Such information will allow researchers to gain a better understanding of the genetic variation within the UK fox population.

"Analysis of the origin of domestic animals is of wide interest and has many practical applications in areas such as agriculture and evolutionary biology. Identification of an ancestor and comparison with the domesticated form allows for an analysis of genetic, physiological, morphological and behavioral effects of domestication. Because fox breeding has been an ongoing process for over a century, differences are expected between farm and wild populations at the chromosomal level"

Polymorphism of Cytogenetic Markers in Wild and Farm Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) Populations - Monika Bugno-Poniewierska et al. (2013)

"For each of the genes investigated specific SNP profiles characteristic only for farm foxes and only for wild foxes were noted. At the same time, specific SNP profiles were noted for wild foxes from North America and from Europe"

Genetic Differentiation of Common Fox (Vulpes Vulpes) - Annals of Animals Science (November 2014)

Farm Foxes & The Silver Rush

The farm fox or 'silver fox' is the domesticated version of the melanistic North American red fox. It is a selectively bred farm animal that exists as a result of 'the silver rush', which is famed to have started on Prince Edward Island in the 1880's. Fox farming began as an alternative to the historic practice of hunting and trapping foxes, being promoted as a means to improve pelt production and quality; inadvertently reducing the huge impact the fur trade was having on native wildlife populations in the process.

"Fur trading between the Indians and the whites of Europe was carried on before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth... as early as 1598... In 1627 Cardinal Richelieu of France founded "The Company of One Hundred Associates" which was to have a monopoly of the fur trade to extend from 1628 to 1643. By this time the fur trade and the lure of gold had attracted the attention of Englishmen... The Dutch had lost their possessions in America in their war with England and thus the new Amsterdam fur trade had come into possession of the British. At this period the names of Radisson and Grossiliers as two of the most important fur traders should be mentioned in the light of subsequent events. These two men worked at times for the company of One Hundred Associates and at other times as independent traders...

Occasionally during this period in the history of the fur trade the trappers and Indians caught what was known to the fur industry as a black or silver black fox. Due to its scarcity and because of the wonderful

luster of its pelt, the black or silver fox pelt always brought a fabulous price. The silver black fox has never

been found on any other continent but North America and is a descendent from the common red fox. It is what is known as a sport or mutation in the animal kingdom. Due to the fact that one silver fox pelt would bring hundreds of dollars more than the common red variety, we can readily see why it was that the first men who conceived of the idea of fur farming should naturally turn to the silver fox.

As early as 1860 John Hadley of Wellington County, Ontario, ranched the first pair of silver foxes but discontinued this attempt after a short time. As to whether Mr. Hadley was successful in this venture,

we do not know but surmise that no young were reproduced or he would not have discontinued the enterprise so soon. Sir Charles Dalton was the next man who became interested in the possibilities of producing silver black foxes under domestic conditions. After several unsuccessful attempts, he purchased a pair of silver foxes from John Martin of Prince Edward Island. Mr. Martin had dug these animals out of a den the year previous but they had failed to breed the first year of captivity. Dalton had better luck and was successful in obtaining two litters from this pair. As some of the pups from these mating's were not up to the standard of their parents, they were pelted. Later Dalton was able to get from Lories Holland, Bedeque, Prince Edward Island, two other pairs of black foxes. In the year of 1890 Mr. Dalton took Mr. Robert T.

Oulton in as a partner and they moved their foxes to Cherry Island, the home of Mr. Oulton...

In 1898 Johann Beitz, Piastre Bay, Quebec, brought silver foxes from Alaska and had some success in breeding these in captivity. L.L. Burrowman, Wyoming, Ontario" is credited with keeping faxes under domestication for twenty years. In 1903 his stock began to increase. During 1910-11 R.E. Hamilton and G.W. and B.J. Gillis introduced the business in Ontario, and they may therefore be regarded as pioneers

in that province. The Alaska fox was first domesticated by J.E. Milligan and George Morrison. Unaware that the silver black fox was being bred in captivity in far-off Prince Edward Island, Morrison, in the interior of Alaska, was busy establishing a strain of foxes known later as the Alaska. According to Morrison's own account he got his inspiration quite accidently, "One day an Indian came into my store to purchase tobacco. He had in a basket three little black foxes that he had dug out from their den on the bank of a river. As soon as I saw these pups it occurred to me that if I could buy them and raise them and if they would breed, I could develop a wonderful business." Two of these pups lived, bred the following season and gave birth to six puppies. Later other foxes were secured from the same source, and these, with the original foxes, formed the foundation of this strain of Alaskan ranch bred foxes."

Economic Aspects of the Silver Fox Industry... in Northern Utah

The History of Fox Farming in the Yukon Territory details how local melanistic North American red foxes were trapped and bred for the fur trade in the region from 1911. Not only did such a venture prove lucrative for those who invested, but it also, "contradicted the general belief that black foxes, like black sheep, are merely freaks." It is reported that the first commercial fox farms began in England and Scotland in the 1920's, set up by ex-servicemen, with foxes imported from Canada.

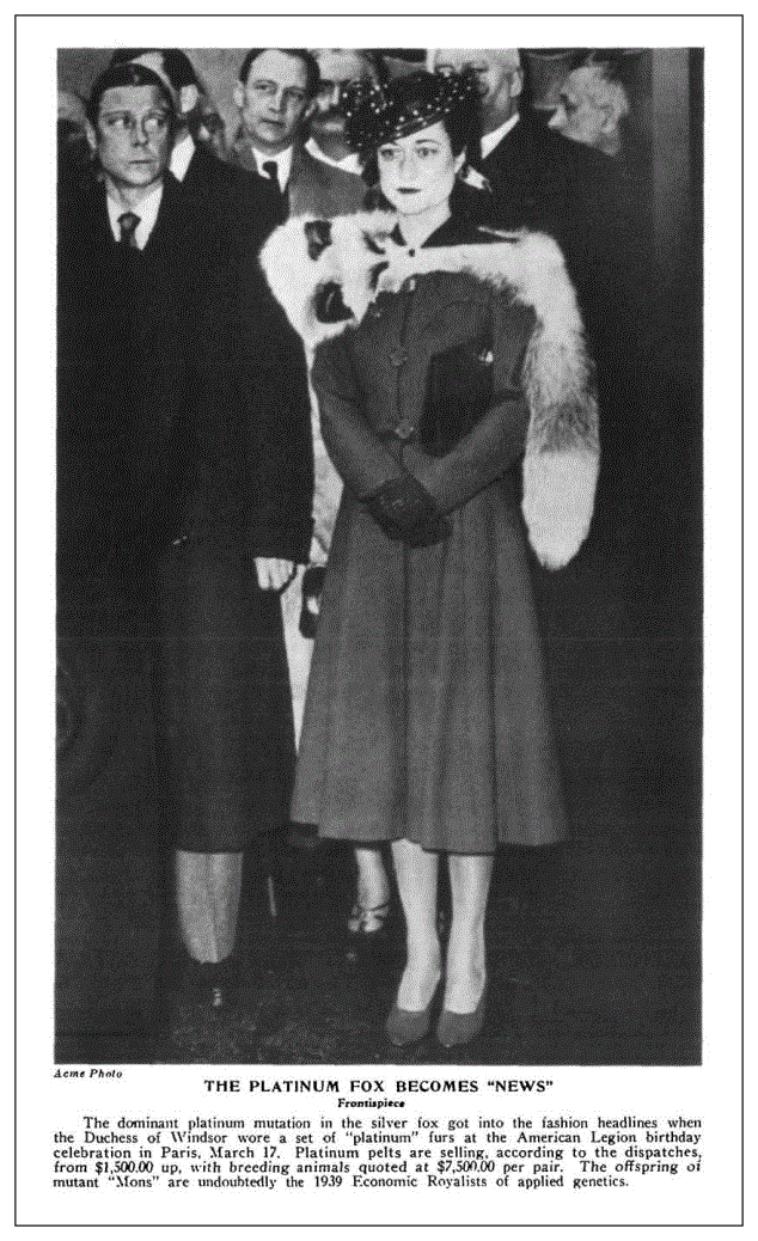

Over the years, as a direct result of selectively breeding foxes for coat colour and quality, new coat colours began to appear. These novel colour mutations were difficult to produce and did not exist in wild populations naturally, resulting in the increased popularity of fox fur as a luxury item and the huge price unique pelts would sell for at the time. Back then, a breeding pair of platinum foxes would cost the equivalent of £1 million. Today, such a pair of foxes can be obtained from breeders for under £1000.

© 1939 Journal of Hereditary - The Platinum Fox Becomes News

The commercial selective breeding of melanistic foxes in captivity by man for the fur trade pre-dates our production of inbred laboratory strains of rodents (early 1900's). In fact, it was the fox farming community that provided the need for formulated and pelleted diets, the development of which then allowed the scientific community to improve the welfare and longevity of laboratory rodents. Fox farmers even contributed to veterinary and animal science directly by adding to our knowledge of genetics and through the development of the first distemper vaccine, which our pets use modern versions of today.

The silver fox's status as a domesticated farm animal is not fully recognised (only the experimental foxes are considered officially domesticated), though it is acknowledged in Canadian and EU literature that farm foxes are to be treated as 'domesticated farm animals' under farming regulations.

While farm foxes have been historically bred for unique colour traits and not for temperament, modern fur farming accepts that foxes which can tolerate human handling have higher welfare standards. As a result, fox farmers in Europe are now required to breed for improved temperament and reduced fear of man.

As a result of their domestication, silver foxes display a much greater variety of polymorphism than what is seen in wild red foxes in the UK;

- silver foxes are slightly larger, with longer hind-limbs,

- have larger, fuller tails and longer white tail tips,

- have shorter, broader faces,

- as well as thicker, longer coats, with a much wider variety of colouration's.

Below is an example of the Georgian Red colour morph. The Georgian colour morph is considered the Russian version of the marbled silver fox, it is a rare colour morph that is a direct product of intensive selective breeding for unique colour traits.

© 2015 DragoNika - White-Red Fox Pup

"The Georgian [fox], also called the snow mutant, was first documented in Russia in 1943. It is a white fox with black spots on the face, back and feet... These foxes are often described as 'freckled'. The gene is incompletely dominant, and is lethal in homozygous condition... These foxes were heavily restricted when they were first discovered during the period of the USSR, and for a time only existed in Russia. They now are present across Europe, but they are not in the North American [or UK] pet trade at this time, except for Russian domesticated foxes imported to the US"

Georgian Fox - Fox Fanatic

Historical records show that the earliest reports of fox farming in the UK can be dated back to the 1800's;

"A more unusual trade to be recorded by the archaeological record is that of silver fox farming. A brick tower (NHER 8023) that stands south of Heath Farm on the Short-Thorn Road supposedly belonged to a post medieval silver fox farm, with the farmer sitting in the tower to watch the foxes"

Parish Summary:Sutton Strawless - Norfolk Heritage Explorer

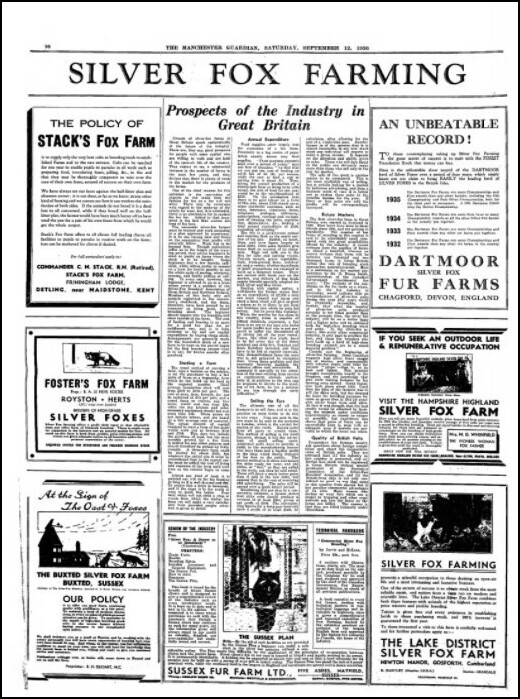

However, the Silver Rush and commercial fox farming wasn't to hit the UK until the early 1900's;

"Seven 'Silver Foxes' are recorded as having been born in the Gardens 1857-1862, and also five hybrids between this species and the European Fox, two in 1832, three in 1870. The farming of foxes for the fur industry started in the British Isles in 1920 and by 1932 there were 115 breeders across the country"

First and Early Breeding Records for Mammals in the UK and Eire: Carnivora (Silver Fox) - The Bartlett Society

"When the demand for fox furs peaked in the 1930's many turned to breeding the coveted varieties, particularly silver, blue, platinum and white (Arctic) fox. Some 150 silver fox fur breeders were listed in the British Fur Trade Yearbook for 1933"

Skin Deep: The Fall of Fur - History Today

Fur farming wasn't the only commercial use of foxes in the UK in the early 1900's. English rat catcher John Wheeldon, trained foxes for 'economic use' by teaching them to assist him and his dogs with providing rat catching services (a practice adopted by the Chinese in 2004 with silver foxes, in order to keep mole rat plagues under control).

© Picture the Past - The Sawmills Ratcatcher

"John Wheeldon, better known as John Gaunt. He lived at Sawmills but worked for the Midland Railway Company, travelling the lines as a rat catcher. He is the only person known to have successfully trained foxes to 'rat' for economic use, and claimed they were better than terriers because they could hold five rats in their mouths at once.

The rat catcher had to be quick because, unlike a terrier, foxes did not kill the rats outright. His best two foxes however, were killed accidentally by gamekeepers. Such was his national fame that he was described in a book as a 'great sportsman great Englishman"

John Wheeldon, The Sawmills Ratcatcher

© Anon. (Ebay 2015) - Norfolk Fur Farm

"I was 20 years old in 1932... I only worked on the farm for a few months during the summer of that year... A driveway along side of the bungalow led down to the Fox Kitchen and the Offices, the kitchen was used for the fox's food, which as far as I can remember consisted of a lot of eggs and baby turkeys, there were a lot them about, and I do remember that the kitchen was spotlessly clean...

The foxes themselves were housed in pens completely made up of chicken wire both round the sides and on the floor, presumably to stop them digging their way out. They were beautiful creatures with black and silver fur. I supposed they were bred for their fur. There must have been just under a hundred as far as I can remember"

Doris Louisa Bohannan nee Peg - At Sheringham Norfolk

Today, the attitude to wearing fur in the UK is very different from what it once was, with fur farming being banned under the Fur Farming (Prohibition) Act 2000 - prohibiting the keeping of animals solely or primarily for the value of their fur. There were 11 fur farms left in the UK just prior to the ban, most of which had ceased breeding foxes many years earlier.

Historic UK Fox Farms: An Interactive Map

This interactive map explores the historical locations of fox farms across the United Kingdom, alongside notable sites in Norfolk and Orkney. Together, these locations tell a story of cultural and agricultural practices spanning centuries, from ancient history to the early 20th-century fur trade.

Key fox farming sites include Snow Belt Farm in Scotland, recognized as the UK’s first fox farm. The Hollywood Silver Fox Farm in Lincolnshire, known for its landmark tort law case, illustrates early public resistance to fox farming. In Halifax, Mytholm Fur Farm is linked to the release of farmed foxes during World War II, which may explain the greater occurrence of melanistic traits in local fox populations. The last reported fox farm, Cocksparrow Fox Farm, located in Coventry, closed in 1982.

- Buxted Silver Fox Farm – Sussex

- Cocksparrow Fox Farm – Warwickshire

- Dartmoor Silver Fox Fur Farms – Devon

- Foster's Fox Farm – Hertfordshire

- Highland Silver Fox Farm – Hampshire

- Hollywood Silver Fox Farm – Co. Wicklow

- Highland Silver Fox Ranch – Lumphanan

- McLelland and Partners – London

- Mytholm Fur Farm – Halifax

- Peregrine Fur Farm – Moretonhampstead

- Saltoun Fox Farm – East Lothian

- Sheringham Silver Fox Farm – Norfolk

- Sidlaw Fur Farm – Perthshire

- Silver Fox Farm – Gloucestershire

- Silver Fox Farming Co-operation – Sussex

- Snow Belt Farm – Alness

- Stacks Fox Farm – Rutland

- Sussex Fur Farm Limited – Sussex

- The Lake District Silver Fox Farm – Gosforth

- The Sussex Fur Farm – East Sussex

- Tingwall Silver Fox Farm – Shetland

© Manchester Guardian - Silver Fox Farming, 1936

In 2000, as a tribute to their historical involvement in the once thriving trade of UK fur production, the Shetland Museum opened an exhibition dedicated to the history of fox and mink farming on the isles, documenting their involvement in the fur trade, as well as the humane farming practices the isles brought to the industry. Since it's peak in the mid-1900's, the fur industry has considerably reduced housing standards compared to what was once considered acceptable, with the original fur farmers keeping their foxes in a similar way to how zoo's and private keepers might today.

It is also interesting to note, that the fur trade began not only as a means to improve and control pelt quality and colour, but it was also hoped to reduce the burden that hunting for fur was placing on wild populations. Given man's attitude towards hunting at the time, combined with the increasing demand for fox fur, it seems possible the North American red fox may have ended up hunted into extinction, had farming not have been able to meet the demand. As it stands, pure native lines of North American red fox are considered a threatened species today; the result of historic practices of hunting and trapping, hybridisation with introduced foxes (both farm foxes and European fox), current human activity and increasing environmental pressures.

© Shetland Museum Archive - Tingwall Silver Fox Farm

The Domesticated Silver Fox

In 1959, Russian scientists Dmitry Belyaev and Lyudmila Trut began an experiment into domestication processes by selectively breeding farm foxes for desired behaviours towards humans; including a line bred specifically for tame behaviour, a line bred specifically for aggressive behaviour and an 'unselected' control group bred for neither tame nor aggressive behaviour (Vulpes vulpes forma amicus). The study began with around 30 dog foxes and around 100 vixens and and demonstrates how not only can behaviour be inherited, but that phenotypical changes can occur during the process of selective breeding solely for desired behavioural traits.

Throughout the experiment, foxes were temperament tested and given a tameness classification level, being graded from 1st-3rd Class based on their results to the testing. Only the top 20% of each generation from the 1st Class group were allowed to became the next seasons breeding stock. Within 10 generations, they were producing foxes that were tame beyond what they had expected from even a Class 1 animal and an Elite Class (known as the 'Domesticated Elite') had to be created, with 18% of foxes making the grade. By 2009, 70-80% of foxes were being graded as 'Domesticated Elite'.

The experiment showed that the foxes are fundamentally different in genetics and behavior compared to their wild counterparts, having a greater ability to cope with stress. A trait that is believed to be the result of a change in the production of stress hormones;

"It is not the case that coat color causes a difference in temperament, but rather that certain physiological processes underlie facets of both coat color and behavior. In particular, the hormones and neurotransmitters involved in the stress response and other behaviors are closely integrated with pigment production. For example, the neurotransmitter dopamine and the hormones noradrenaline and adrenaline, which are involved in the stress response, have the same biochemical precursor as the melanin pigments (Anonymous 1971, Ferry and Zimmerman 1964).

In addition, dopamine directly influences pigment production by binding to the pigment-producing cells (Burchill et al. 1986). Dopamine indirectly influences pigment production by inhibiting pituitary melanotropin, also known as melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH), which is responsible for stimulating pigment cells to produce pigment (Tilders and Smelik 1978)"

Jennifer Ormond, MA - Quora, 2015

Given that the parent population of experimental foxes were obtained from North American fur farms and that there are only forty genes found to differ between domesticated and non-domesticated farm-raised foxes (with 2,700 genes difference between the wild foxes and either set of farm-raised foxes), it makes sense that all sliver foxes display phenotypes and behavioural traits not seen in wild foxes, despite the different forms of domestication. However, there are further differences between those foxes scientifically domesticated for tameness and their fur farm counterparts;

- Tame, dog-like behaviours (whining for attention, licking, tail-wagging, playfulness, and barking),

- shorter legs, shorter and curled tails* and spotted fur,

- narrower skulls and shorter snouts than that of wild foxes,

- females began to come into heat twice a year instead of just once as in the case of wild foxes, also,

- tame fox cubs opened their eyes sooner and developed a fear response later than wild fox cubs.

*Curled tails (as well as "floppy ears"), while once thought to be the result of domestication processes, was eventually considered an unwanted mutation that had been inadvertently selected for in the process of domestication. As a result, it is not a trait seen in the experimental fox population today.

The foxes in this experiment have been selectively bred for over 60 generations for their calm temperament and ability to tolerate man. They are considered scientifically 'domesticated pets' as a result of the process that has occurred; unlike that of farmed silver foxes, which have not undergone the same process.

Lyudmila Trut and fox scientist Anna Kukekova continue the legacy after Dmitry Belyaev's death in 1985. The foxes continue to be bred at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics for scientists to better understand the process of domestication, but they are now also sold (neutered) to vetted clients (at the cost of several thousand pounds), as a means to fund the continuation of the experiment after it hit financial hardship. In taking such measures, they have been able to continue this valuable and long-standing research project.

Siberian fox scientist Irina Mukhamedshina trained her domesticated fox Anna (above), after obtaining her from the Institute of Cytology and Genetics as a pet of her own. Anna was as obedient as any dog and was able to master some amazing skills in her time with Irina. Sadly however, Anna escaped one day and was not seen again.

The Siberian Cupcakes - Sophie, Boris, Maks, Viktor and Mikhail, were also bred at the Institute and now live as ambassador animals at the JAB Canine and Education Centre in the USA. Assisting in research that will help further scientific understanding of domestication, the red fox genome and disease development in both humans and animals.

To date, there are no Russian domesticated foxes in the UK. However, they are available for purchase for those with the knowledge, means and funds. It costs around £15-20k to purchase and import a domesticated pet fox, which is a stark difference from the cost of obtaining a regular farm fox.

Pet Foxes in the UK

The practice of keeping foxes in captivity is nothing new in the UK. They have been kept for commercial purposes and as pets throughout history (such as for rat catching, fur production, for use in film and media, as educational animals or when rehabilitation and release have not been possible) and people still keep foxes in the UK today, both wild animals that cannot be released for welfare reasons and the silver foxes bred to be kept as exotic pets and animal ambassadors. Documentation reveals that from the middle of the 17th century, "for the better part of two hundred years", foxes were a common pet kept by peers at the elite Winchester College. There is even evidence that the practice of keeping foxes may date back to as early as 14,000 BC elsewhere in the world.

It is important to note that wild foxes which cannot be rehabilitated and released are not the same as the domesticated silver foxes that exist as a result of the fur trade. If you are concerned about the welfare of a wild fox or wish to assist wild foxes in need of rehabilitation and release, then please contact The Fox Rescuers or The Fox Project for more information.

The silver foxes kept in the UK are not 'domesticated pets' as they have not been selectively bred for tame behaviour towards humans until recently. They are instead, 'domesticated farm animals' that have been selectively bred for coat colour and quality only. These farm foxes are not the same as the experimental foxes people think of when pet foxes are discussed, nor are they the same as the native wild animals that are kept as pets because they cannot be released.

"Although within Canidae only the dog has an ancient history of domestication, the farm-breeding of red foxes began in Eastern Canada in the late 19th century. Conventional farm-bred foxes live in close human proximity, yet they typically respond to humans with fearful aggression"

Four Structural Variants Associated With Human-Direct Sociability In Dog Are Not Found In Tame Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes), (2019)

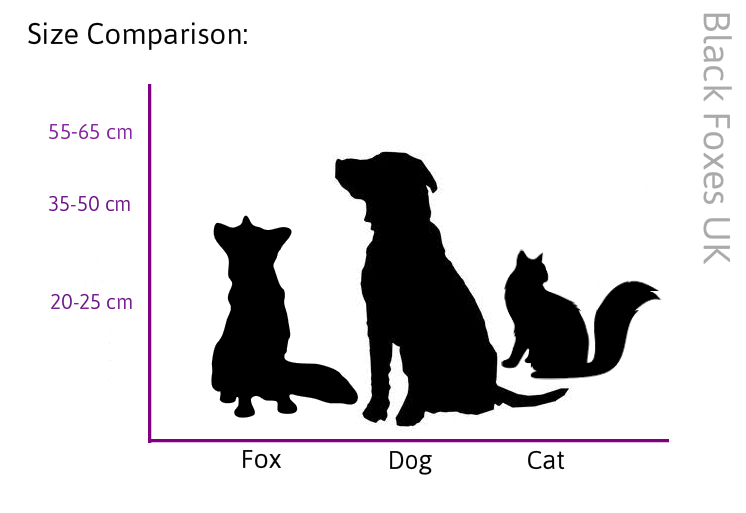

While they are often compared to dogs and cats, silver foxes do not behave like either. Instead, their behaviour is uniquely vulpine; independent, strong-willed and defensive. Which is why keeping foxes is considered a specialist hobby for those with specific interests in exotic animal education, management and behaviour. Temperament-wise, farm foxes could be considered similar to those 'unselected foxes' in the domestication experiment, which were selected for neither tame nor aggressive behaviour and displayed traits from both the tame and aggressive groups, (vocal behaviour in tame, aggressive & unselected foxes).

It requires a lot of time, knowledge and resources to keep exotic pets correctly. Out of all the exotic pets kept, foxes are one of the more difficult species to keep due to their curious and cunning nature. They have many natural behavioural traits that most would consider undesirable in a pet, from their pungent smell to their destructive and territorial tendencies. They are long lived (living up to 10-12 years in captivity), are great escape artists (requiring a secure enclosure) and they are difficult to lead and litter train. They also require a specialist diet, specialist vets and lots of species specific enrichment.

However, for specialist keepers prepared to dedicate their lives to gaining knowledge and understanding on these animals, they can be fun and fascinating companions, as demonstrated below;

The Low-Down on Fox Keeping:

While it is not common for people to come across a silver fox for sale or in need of rehoming in the UK, it does occur, as they are legally bred and sold in the UK without restriction. Black Foxes UK estimates that anywhere between 500 (5 breeders, averaging 5 cubs per litter, over 20 years) and 2,000 silver foxes (20 breeders, averaging 5 cubs per litter, over 20 years) were sold as exotic pets in the UK between 2000 and 2020.

Exotic pets like foxes are a lot more difficult to keep in comparison to other species of exotic pet. Caring for a silver fox costs around £17,000 over it's lifetime, with an initial expense of around £3,000 - £4,000 in the first year (purchase cost, enclosure, safety equipment, diet, enrichment, vaccinations and neutering). It is not possible to obtain exotic pet insurance for silver foxes; and as foxes are curious animals that are highly accident prone, it is advised to have a savings account or credit card set aside, which can be used to cover veterinary costs in the event of an emergency.

Foxes are definitely not a species recommended for novice animal keepers and even experienced keepers can find them a struggle at times (especially over mating season). The silver foxes bred in the UK are also not as bold as those bred elsewhere and they generally do not make suitable at-home companion animals, being more suited to exotic animal education facilities.

What To Know About Keeping Foxes:

- They smell – Foxes have a strong, distinctive odour that can be difficult to remove.

- They can be noisy – Foxes are vocal animals and can make loud, 'blood-curdling' sounds.

- They need a very secure outdoor enclosure – Foxes are escape artists, a secure enclosure is essential.

- They are NOT house pets – Foxes do not behave like dogs or cats, they are uniquely vulpine.

- They climb and dig – Foxes need lots of species-specific enrichment and stimulation.

- They are not pack animals like dogs - Foxes require lots of training and handling can be difficult.

- Temperament varies – Each fox has a unique personality. They are more like feral cats than pet dogs.

- Foxes will bite – A fox's teeth sharp teeth can very easily draw blood, and bites are not uncommon.

- They rarely use a litter tray – Foxes do not litter train well, as they use excrement for communication.

- Be honest about your suitability – Fox keeping is certainly not for everyone.

If you do consider keeping a domestic silver fox as a pet, please ensure you do your research. There is little support and very few options when it comes to re-homing silver foxes in the UK. You must be certain you can take on the commitment before making any decisions and you must adequately invest in the equipment required to keep them effectively, prior to bringing one home.

People will judge you. Be prepared for it, and recognise why public opinion may not be in your favour. When discussing fox care, be truthful and transparent—don’t sugar-coat or glorify the reality.

Our Stance on Fox Keeping:

At Black Foxes UK we accept the silver fox is legally bred and kept here. We also accept our social responsibility towards the domesticated animal we helped to create and understand the benefits and risks it's continued existence presents. We only hope that those who do choose to keep silver foxes, do so responsibly and with the highest welfare goals in mind.

While we feel the place of the silver fox is limited and that keeping silver foxes ought to be a licensed activity (as occurs in other parts of the world), we feel strongly that they are owed some place within our society. In the absence of licensing and because there is limited information out there on the needs of captive foxes outside of the farm or laboratory; we supply information on basic care, health and safety precautions, diet and nutrition, as well as a list of websites on silver foxes and online courses, for those seeking more information.

Ultimately, we aim to inform and educate the general public about the domesticated silver fox and it's place as a commercial product within our society, supporting silver fox keepers (private or organisational) in meeting their needs to the highest possible (scientifically backed) standards. Helping to ensure and improve the welfare and security of the silver fox both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world.

© 2015 Peter Macdiarmid - Getty Images

Regulations relating to foxes in the UK:

- Protection of Animals Act 1911

- Performing Animals Act 1925

- The Pet Animals Act 1951

- The Abandonment of Animals Act 1960

- Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981

- Wild Mammals Protection Act 1996

- Fur Farming (Prohibition) Act 2000

- Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2002

- Protection of Wild Mammals (Scotland) 2002

- Fur Farming (Prohibition) (Scotland) Act 2002

- Hunting Act 2004

- Animal Welfare Act 2006

- Infrastructure Act 2015

- The Animal Welfare (Licensing of Activities Involving Animals) (England) Regulations 2018

UK Legislation on Keeping Foxes:

Foxes are given very little protection under UK law. Partly because of the historical practice of fox hunting and fox farming and partly due to increasing population numbers and the resulting conflicts with man. As a result, it remains legal to humanely trap and kill foxes as a form of pest control. The lack of knowledge on the existence of the domesticated silver fox means that escaped pets are often misidentified as being native wild foxes, putting them at an increased risk from accidental death or injury.

Being a native species, it has always been legal to keep foxes (vulpes vulpes) under certain exceptions, providing certain welfare regulations are met. Throughout history people have taken on and rehabilitated foxes in need and the ban on fur farming in 2000, together with changes to legislation in keeping exotic pets in 2007 (Dangerous Wild Animals Act (1976) Modification Order 2007), resulted in a greater understand that silver foxes existed and that it was legal to keep and breed them, providing it was not to kill them for their fur.

Although they are both a different subspecies, domesticated silver foxes and native red foxes are considered the same from the viewpoint of UK law, they are both vulpes vulpes and the law applies to each subspecies without distinction. That being said, interpretation of the law on foxes differs depending on the age and health of the animal, as well as if the animal was captive bred or wild caught;

-

It is considered breech of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 to capture healthy wild foxes for the purpose of keeping them contained in captivity unless there is a medical need to do so for treatment.

-

It is considered breech of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 to breed "rescued" or "wild-caught" native foxes (and their offspring) in captivity. All reasonable attempts to rehabilitate such offspring for release must be made - except in the case of non-native animals or their hybrids, which cannot be released. While it is not strictly a legal requirement, for welfare reasons, wild foxes that cannot be rehabilitated for release require neutering, or should be kept in same sex groups if neutering is not possible.

-

It is considered breech of both the Animal Welfare Act 2006 and the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 to intentionally or unintentionally release into the wild; domesticated animals, captive wild animals which cannot be released for welfare reasons and non-native animals or their hybrids.

-

It is legal to humanely trap both sick or injured wild foxes and captive bred foxes (with permission of the landowner), if the intention is for treatment, rehabilitation and release (in the case of wild foxes), or if the intention is to return them to captivity (in instances of domesticated animals, captive wild animals that cannot be released for welfare reasons and non-native animals ).

Anomalous Red Foxes In the UK

A photo catalogue of anomalous Red foxes reported in the UK. Images of deceased foxes included within.

Many of the images below were provided directly to Black Foxes UK and we would like to say a special thank you to those who have shared their images with us. The remaining images were sourced through the media and via social media.

A catalogue of videos of anomalous Red foxes reported in the UK: